In this post, I want to discuss the importance of designing and implementing micro-segmentation in Azure networks.

Repeating The Same Mistakes

In 2002-2003, the world was being hammered by malware. So much so, that Microsoft did a reset on their Windows development processes and effectively built a new version of Windows XP with Windows XP Service Pack 2. The main security feature of that release was the Windows Firewall – the purpose of this was to isolate each Windows machine in the network by default. It’s a pity that nearly every Windows admin then used Group Policy to disable the Windows Firewall!

Times have moved on and so have the bad guys. Malware isn’t just an anarchist or hobby activity. Malware is a billion-dollar business (ransomware/data theft) and a military activity. Naturally, defences have evolved .. wait .. no … most admins/consultants are still deploying networks that your Daddy/Mommy deployed 22 years ago but I’ll deal with that in another post.

Instead, I want to discuss a part of the defensive solution: micro-segmentation.

Assume Penetration

We must assume that the attacker will always find a way in. Not every attack will be by Sandra Bullock clicking some magical symbol on a website to penetrate the firewall. Most attacks have relatively simple vectors such as stealing a password, hash highjacking, or getting an accountant to open a PDF. Determined attackers aren’t just “driving by”; they will look for an entry. Maybe it’s malware in vendor software that you will deploy! Maybe, it’s a vulnerability in open-source software that your developers will deploy via GitHub? Maybe a managed service provider’s Entra ID tenant has been penetrated and they have Lighthouse access to your Azure subscriptions? Each of those examples bypasses your firewall and any advanced scanning features that it may have. How do you stop them?

Micro-Segmentation

Let me conjure an image for you. A submarine is on patrol. It has a wartime mission. The submarine is always under orders to continue that mission. The submarine is detected by the enemy and is attacked. The attack causes damage which creates a flood. If left unchecked, the flood will sink the ship. What happens? The crew is trained to isolate the flood by sealing the leaking compartment – doors are slammed, seals are locked, and the water is contained in that compartment. Sure, the sailors and ship functions in that compartment are dead, but the ship can continue its mission.

That is a way to visualise micro-segmentation.

Microsoft Zero-Trust

Microsoft has a relatively small collection of documentation on zero-trust architecture for Azure. There are 3 useful bullet points:

- Be ready to handle attacks before they happen.

- Minimize the extent of the damage and how fast it spreads.

- Increase the difficulty of compromising your cloud footprint.

Let’s expand on that a little.

Be Ready

You will be ready for an attack because you assume that you already are under attack. You don’t wait to deploy security systems and configurations; you design them with your workloads. You deploy security with your workloads. You maintain security with your workloads.

Increase The Difficulty of Compromising Your Cloud Footprint

You should put in the defences that are appropriate to your actual risks and ability to install/manage. A bad example is a medical organisation choosing a more affordable firewall to save a few bucks – this is the sort of organisation that will be targeted.

Minimise The Extent of Damage

This can also be referred to as minimising the blast zone. You want to limit how much damage the bad guys cause, just like the submarine limited flooding to the damaged compartment. This means that we make it harder to get from any one point on the network to the next.

It’s one thing to put in the security defences, but you must also:

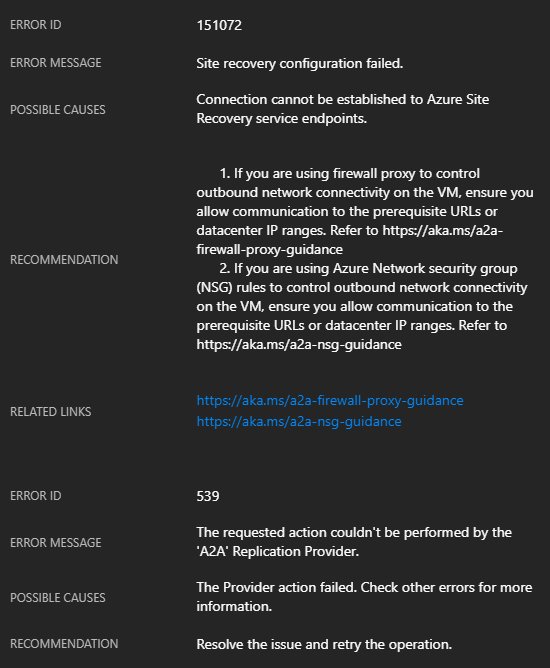

- Enable/configure the security features: it shocks me how many organisations/consultants opt not to or don’t know how to enable essential features in their security solution.

- Monitor your security systems: If we assume that the attacker will get in, then we should monitor our security features to detect and shut down the attack. Again, I’m shocked every time I see security features in Azure that have no logging or alerting enabled.

Microsoft lays out a path to zero-trust where step number one is network segmentation. The basic pattern is laid out:

Applications are partitioned to different Azure Virtual Networks (VNets) and connected using a hub-spoke model

Microsoft uses the term “application”. I prefer the term “workload”. Some, like ITIL, might use the term “service”. A workload is a collection of resources that work together to provide a service to or for the organisation. Maybe it’s a bunch of Azure resources that create a retail site. Maybe it’s a CRM system. Maybe it’s an identity management & governance workload.

The pattern that Microsoft is recommending is one that I have been promoting through my employer for the last 6 years. Each workload gets a dedicated “small” virtual network. The workload VNet is peered with a hub (and only the hub by default). The hub firewall provides isolation and deeper inspection than NSGs can offer.

Step 4 tells us:

Fully distributed ingress/egress cloud micro-perimeters and deeper micro-segmentation

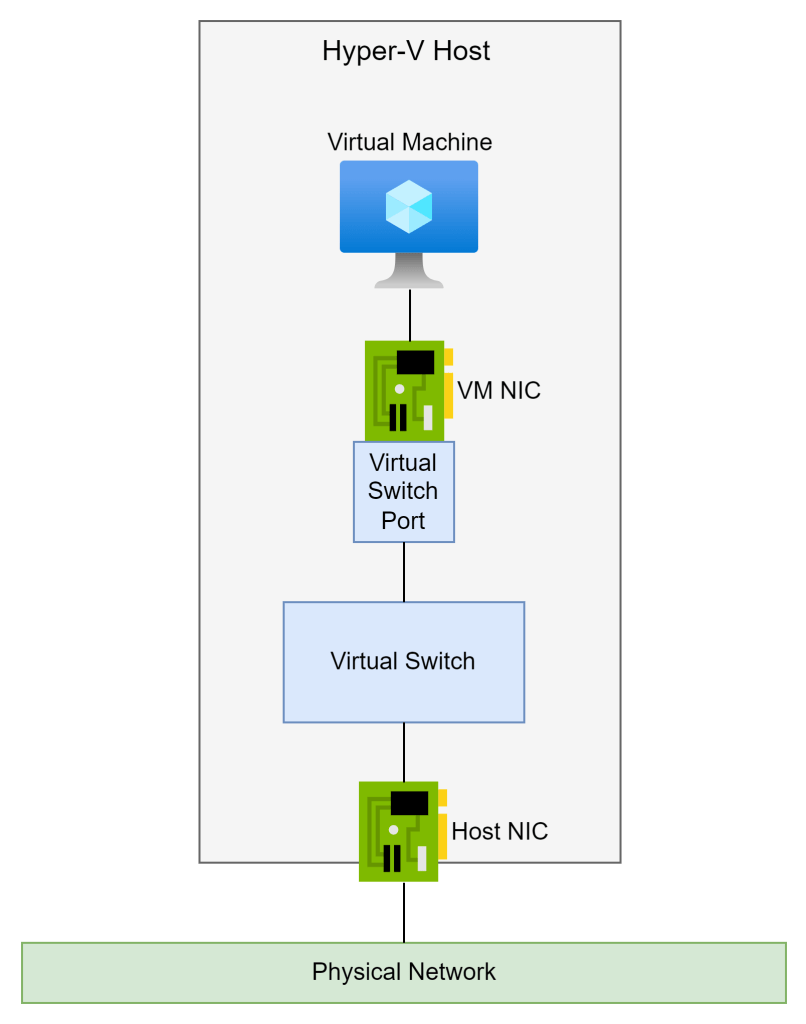

NSGs micro-segment the single or small set of subnet(s) in the VNet, restriocting resource-to-resource connections to just what is required. Isolation is now done centrally and at the NIC, thanks to NSGs. You should also consider network protections on PaaS resources such as Storage Accounts or Key Vaults.

If we revisit the submarine comparison, the workload-specific virtual network is one of the compartments in the boat. If there is a leak (an attack), the NSGs limit or slow down expansion in the subnet(s). The firewall isolates the workload/compartment from other workloads/compartments and the Internet by default to prevent command and control or downloads by the attacker. Deeper firewall inspection searches for attack patterns.

Don’t Forget Monitoring

Microsoft zero-trust has more than just networking. One other step I want to highlight is monitoring/alerting because it ties into the micro-segmentation features of networking. Consider the mechanisms we can put in place:

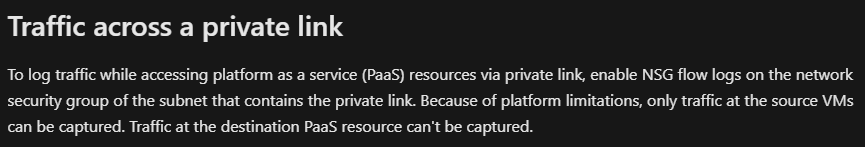

- Paas resource firewalls with logging

- NSG with VNet Flow Logging

- (Azure) Firewall with logging for firewall rules and deep inspection features (Azure Firewall has Threat Intelligence and IDPS).

Each of those barriers or detection systems can be thought of as a string with a bell on it. The attacker will tickle or trip over those strings. If the bell rings, we should be paying attention. When you fail to put in the barriers or configure monitoring then you don’t know that the attacker is there doing something – and we assume that the attacker will get in and do something – so aren’t we failing to do our job?

It’s Not Just Me Telling You

You can say “There goes Aidan, rattling on about micro-segmentation. Why should I listen to him?”. It would be one thing if it were just me sharing my opinion on Azure network security but what if others told you to do the same things?

Microsoft tells you to implement micro-segmentation. The US NSA tells you to do it. The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security tells you to do it. The UK NCSC tells you to do it. I could keep googling (binging, of course) national security agencies and I’d find the same recommendation with each result. If you are not implementing this security technique designed for today’s threats (not for the Blaster worm of 2003) then you are not only not doing your job but you are choosing to leave the door open for attackers; that could be viewed very poorly by employers, by shareholders, or by informed compliance auditors.