I see many people implementing classic network security designs in Azure. Maybe there’s DMZ and an internal virtual network. Maybe they split Production, Test, and Dev into three virtual networks. Possibly, they do a common government implementation – what Norway calls “Secure Zone”. I’m going to explain to you why these network designs offer very little security.

I have written this post as a contribution to Azure Spring Clean 2025. Please head over and check out the other content.

Essential Reading

This post is part of a series that I’ve been writing over several weeks. If you have not read my previous posts then I recommend that you do. I can tell that many people assume certain things about Azure network based on designs that I have witnessed. You must understand the “how does it really work” stuff before you go any further.

- Azure Virtual Networks Do Not Exist

- How Do Network Security Groups Work?

- Beware Of The Default Rules In Network Security Groups

- How Many Subnets Do I Need In An Azure Virtual Network?

- Routing Is The Security Cabling of Azure

- How Does Azure Routing Work

- How Many Azure Route Tables Should I Have?

- Micro-Segmentation Security In Azure Networks

A Typical Azure Network Design

Most of the designs that I have encountered in Azure, in my day job and as a community person who “gets around”, are very much driven by on-premises network designs. Two exceptions are:

- What I see produced by my colleagues at work.

- Those using Enterprise Scale from the Microsoft Cloud Adoption Framework – not that I recommend implementing this, but that’s a whole other conversation!

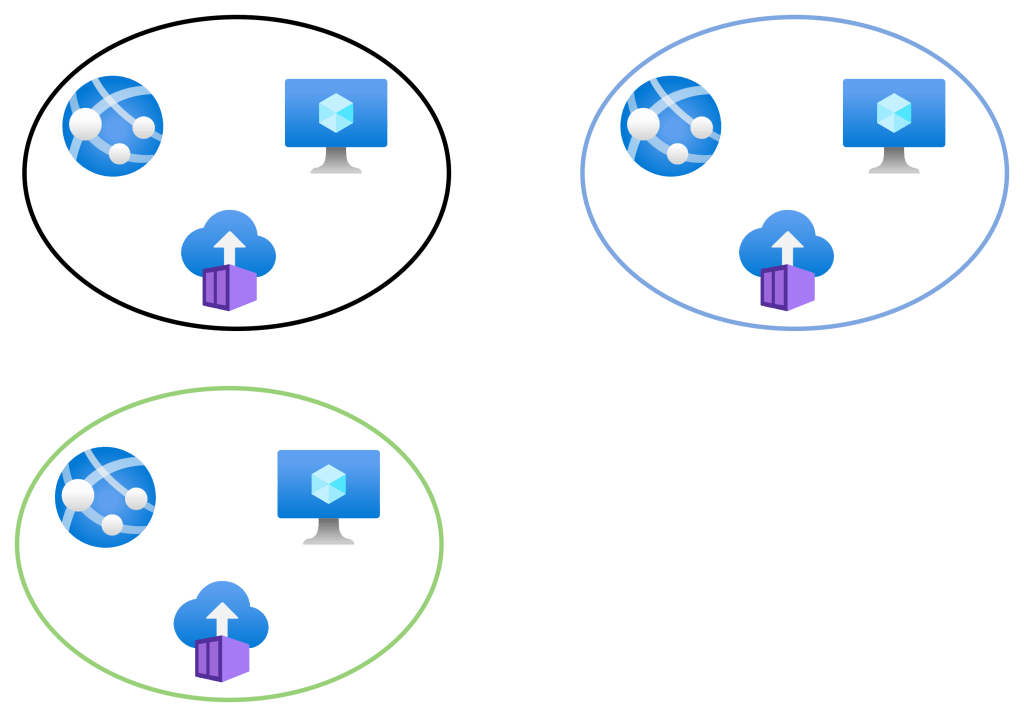

What I mostly observe is what I like to call “big VNets”. The customer will call it lots of different things but it essentially boils down to a hub-and-spoke design that features a few large virtual networks that are logically named:

- Dev, Test, and Production

- DMZ and private

- Internal and Secure

Workload: A collection of resources that provide a service. For example, an App Service, some Functions, a Redis cache, and a database might make a retail system. The collection of resources is a workload, united in their task to provide a service for the organisation.

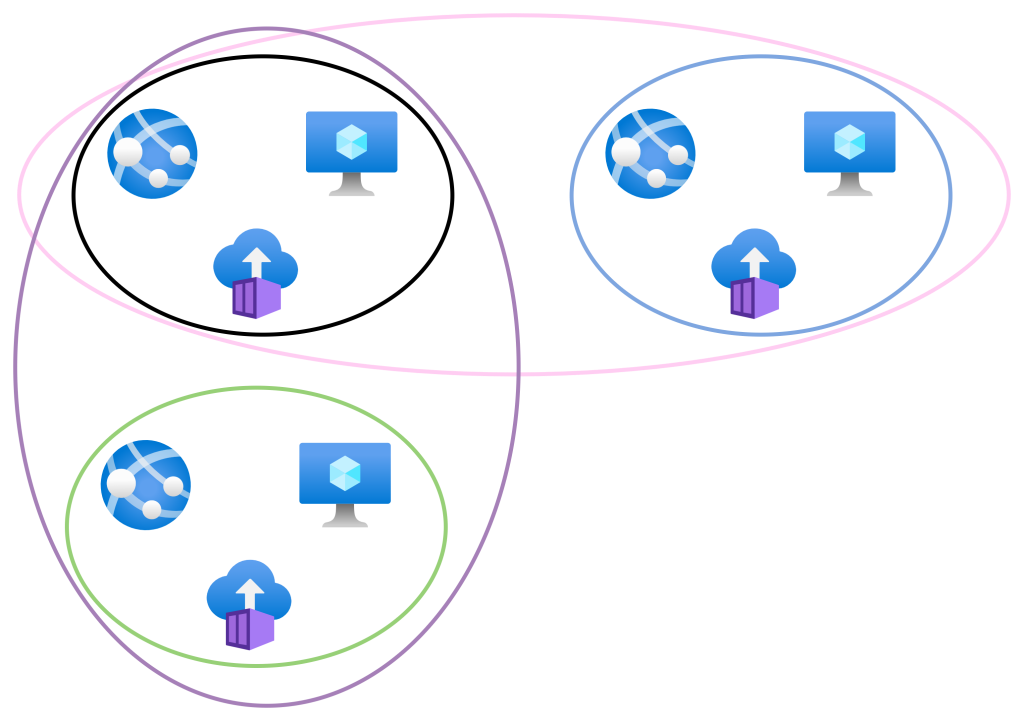

You get the idea. There are a few spoke virtual networks that are each peered to a hub.

The hub is a transit network, enabling connectivity between each of the big VNets – or “isolating them completely” – except for where they don’t (quite real, thanks to business-required integrations or making the transition from testing to production easier for developers). The hub provides routing to Azure/The Internet and to remote locations via site-to-site networking.

If we drill down into the logical design we can see the many subnets in each spoke virtual network. Those subnets are logically divided in some way. Some might do it based on security zones – they don’t understand NSGs. Some might have one subnet per workload – they don’t know that subnets do not exist. Each subnet has an NSG and a Route Table. The NSG “micro-segments” the subnet. The Route Table forces traffic from the subnet to the firewall – the logic here can vary.

Routing & Subnet Design

Remember three things for me:

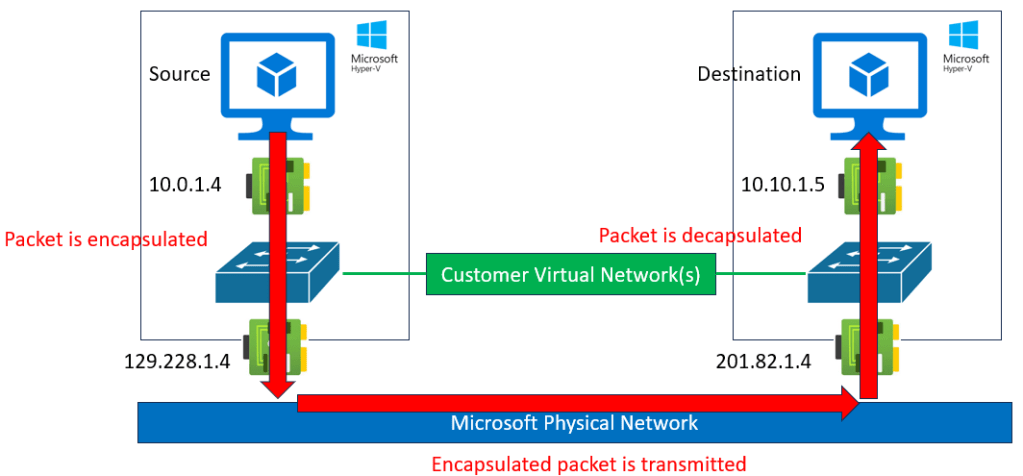

- Virtual networks and subnets do not exist – packets go directly from sender to receiver in the software-defined network.

- Routing is our cabling when designing network security.

- The year is 2025, not 2003 (before Windows XP Service Pack 2 introduced Windows Firewall to the world).

There might be two intents for routing in the legacy design:

- Each virtual network will be isolated from the others via the hub firewall.

- Each subnet will be isolated from the others via the hub firewall.

Big VNet Network Isolation

Do you remember 2003? Kid Rock and Sheryl Crow still sang to each other. Avril Lavigne was relevant (Canada, you’re not getting out of this!). The Black Eyed Peas wanted to know where the love was because malware was running wild on vulnerable Windows networks.

I remember a Microsoft security expert wandering around a TechEd Europe hall, shouting at us that network security was something that had to be done throughout the network. The edge firewall was like the shell of an egg – once you got inside (and it didn’t matter how) then you had all that gooey goodness without any barriers.

A year later, Microsoft released Windows XP/Windows Server 2003 Service Pack 2 to general availability. This was such a rewrite that many considered it a new OS, not a Service Pack – what the kids today call a feature update, a cumulative update, or an annual release. One of the new features was Windows Firewall, which was on by default and blocked stuff from getting into our machines unless we wanted that stuff. And what did every Windows admin do? They used Group Policy to turn Windows Firewall off in the network. So malware continued, became more professional, and became ransomware.

Folks, it’s been 21 years. It’s time to harden those networks – let the firewall do what it can do and micro-segment those networks. Microsoft tells you to do it. The US NSA tells you to do it. The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security tells you to do it. The UK NCSC tells you to do it. Maybe, just maybe, they know more about this stuff than those of you who like gooey network insides?

Big VNet Subnet Isolation

The goal here is to force any traffic that is leaving a subnet to use the hub firewall as the next hop. In my below example, if traffic wants to get from Subnet 1 to Subnet 2, it must first pass through the firewall in the hub. A Route Table is created with a collection of User-Defined Routes (UDR) such as shown below.

Each UDR uses Longest Prefix Match to force traffic to other subnets to route via the firewall. You don’t see it in the diagram, but there would also be a route to 0.0.0.0/0 via the firewall, including any prefix outside of this virtual network, except the hub (Longest Prefix Match selecting the System route created by peering with the hub).

Along comes the business and they demand another workload or whatever. A new subnet is required. So you add that subnet. It’s been a rough Friday and the demand came right before you went home. You weren’t thinking straight and .. hmm … maybe you forgot to update the routing.

Oh it’s only one Route Table for Subnet 4, right? Em, no; you do need to add a route table to Subnet 4 with prefixes to subnets 1-3 and 0.0.0.0/0. But that only affects traffic leaving Subnet 4.

What you forget is that routing works in two ways. Subnets 1-3 require a UDR each for Subnet 4, otherwise traffic from Subnets 1-3 will route directly to Subnet 4 and the deeper inspection of the firewall won’t see the traffic. Worse, you probably broke TCP communications because you set up an asynchronous route and the stateful hub firewall will block responses from Subnet 4 to Subnets 1-3.

Imagine this Production VNet with 20, 30, or 100 subnets. This routing update is going to be like like manual patching – which never happens.

One of the biggest lessons I can share in secure network design is KISS: keep it simple, stupid. Routing should be simple, and routing should be predictable when there is expansion/change, because routing is your cabling for enforcing or bypassing network security.

Network Security Group Design

As a consultant, I often have a kickoff meeting with a customer where they stress how important security is. I agree – it’s critical. And then I get to see their network or their plans. At this point, I shouldn’t be surprised but I always am. Some “expert” who passed an Azure certifcation exam or three implements a big VNet design. And the NSGs – wow!

What you’ll observe is:

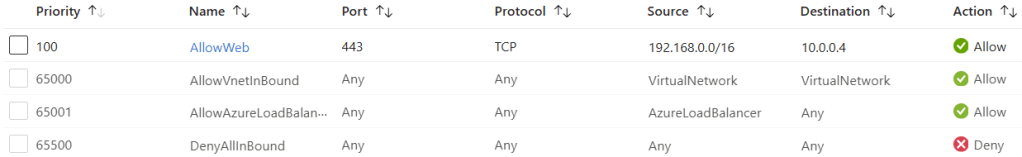

- They implement subnets as security zones, when the only security zoning in Azure is the NSG. NSG rules, processed on the NIC, are how we allow/deny incoming or outgoing traffic at the most basic level. In the end, there are too many subnets in an already crowded big VNet.

- The NSG either uses lots of * (any) in the sources and destinations leading to all sorts of traffic being allowed from many locations.

- They think that they are blocking all incoming traffic by default but don’t understand what the default rule 65000 does – it lets every routable network (Azure & remote) in.

- They open up all traffic inside the subnet – who cares if some malware gets in via devops or a consultant who uploads it via a copy/paste in RDP?

And they’ll continue to stress the importance of security.

Shared Resources In The Hub

This one makes me want to scream. And to be fair, Microsoft play a role in encouraging this madness – shame on you, Microsoft!

The only things that should be in your hub are:

- Virtual Network Gateways

- Third-party routers and Azure Route Server

- The firewall

- Maybe a shared Azure Bastion with appropriate minmised RBAC rights

Don’t put DNS servers here. Don’t put a “really important database” in the hub. Don’t put domain controllers in the hub. Repeat after me:

I will not place shared resources in the hub

Everything is a shared resource. Just about every workload shares with other workloads. Should all shared resources go in the hub? What goes in the spokes now?

“Why?” you may ask. Remember:

- By default, everything goes straight from source to destination

- Routing is our way to force traffic through a firewall

- When you peer two VNets, a new System route enables direct connectivity between NICs in the two VNets.

People assume that a 0.0.0.0/0 route includes everything, but Longest Prefix Match overrides that route when other routes exist. So, if you place a critical database in the hub, spokes will have direct connectivity to that database without going through the firewall and any advanced inspection/filtering services that it can offer – and vice versa. In other words:

- You opened up every port on the critical resource to every resource in every spoke.

- You created an open bridge between every spoke.

And the fact is that putting something in the hub doesn’t make it “more shared” (how is it less shared than something in a spoke?) or faster (software-defined networking treats two NICs in peered VNets as if they were in the same VNet).

Those clinging to putting things in the hub will then want more routes and more complexity. What happens when the organisation goes international and adds hub & spoke deployments in other regions? What should be a simple “1 peering & 1 route” solution between two hubs will expand into routes for each hub subnet containing compute.

Everything is shared – that’s modern computing. Place your workloads into spokes, whether they are file shares, databases, domain controllers, or DNS servers/Private Resolvers. They will work perfectly well and your network will function, be more secure, simpler to manage/understand, and the security model will be more predictable.

Wrapping Up

This is a long post. There is a good chance that I just spat in the face of your cute lil’ baby Azure network. I will be showing you alterantives in future posts, building up the solution a little at a time. Until then, KISS … keep it simple, stupid!