How do you plan a hub & spoke architecture? Based on much of what I have witnessed, I think very few people do any planning at all. In this post, I will explain some essential things to plan and how to plan them.

Rules of Engagement

Microsoft has shared some concepts in the Well-Architected Framework (simplicity) and the documentation for networking & Zero Trust (micro-segmentation, resilience, and isolation).

The hub & spoke will contain networks in a single region, following concepts:

- Resilience & independence: Workloads in a spoke in North Europe should not depend on a hub in West Europe.

- Micro-segmentation: Workloads in North Europe trying to access workloads in West Europe should go through a secure route via hubs in each region.

- Performance: Workload A in North Europe should not go through a hub in West Europe to reach Workload B in North Europe.

- Cost Management: Minimise global VNet peering to just what is necessary. Enable costs of hubs to be split into different parts of the organisation.

- Delegation of Duty: If there are different network teams, enable each team to manage their hubs.

- Minimised Resources: The hub has roles only of transit, connectivity, and security. Do not place compute or other resources into the hub; this is to minimise security/networking complexity and increase predictability.

Management Groups

I agree with many things in the Cloud Adoption Framework “Enterprise Scale” and I disagree with some other things.

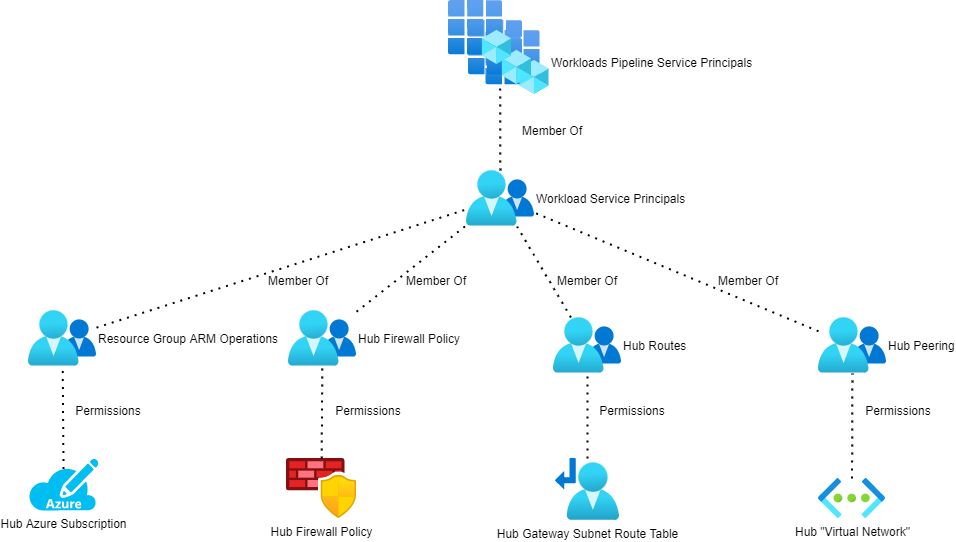

I agree that we should use Management Groups to organise subscriptions based on Policy architecture and role-based access control (RBAC – granting access to subscriptions via Entra groups).

I agree that each workload (CAF calls them landing zones) should have a dedicated subscription – this simplifies operations and governance like you wouldn’t believe.

I can see why they organise workloads based on their networking status:

- Corporate: Workloads that are internal only and are connected to the hub for on-premises connectivity. No public IP addresses should be allowed where technically feasible.

- Online: Workloads that are online only and are not permitted to be connected to the hub.

- Hybrid: This category is missing from CAF and many have added it themselves – WAN and Internet connectivity are usually not binary exclusive OR decisions.

I don’t like how Enterprise Scale buckets all of those workloads into a single grouping because it fails to acknowledge that a truly large enterprise will have many ownership footprints in a single tenant.

I also don’t like how Enterprise Scale merges all hubs into a single subscription or management group. Yes, many organisations have central networking teams. Large organisations may have many networking teams. I like to separate hub resources (not feasible with Virtual WAN) into different subscriptions and management groups for true scaling and governance simplicity.

Here is an example of how one might achieve this. I am going to have two hub & spoke deployments in this example:

- DUB01: Located in Azure North Europe

- AMS01: Located in Azure West Europe

Some of you might notice that I have been inspired by Microsoft’s data centre naming for the naming of these regional footprints. The reasons are:

- Naming regions after “North Europe” or “East US” is messy when you think about naming network footprints in East US2, West US2, and so on.

- Microsoft has already done the work for us. The Dublin (North Europe) region data centres are called DUB05-DUB15 and Microsoft uses AMS01, etc for Middenmeer (West Europe).

- A single virtual network may have up to 500 peers. Once we hit 500 peers then we need to deploy another hub & spoke footprint in the region. The naming allows DUB02, DUB03, etc.

The change from CAF Enterprise Scale is subtle but look how instantly more scalable and isolated everything is. A truly large organisation can delegate duties as necessary.

If an identity responsible for the AMS01 hub & spoke is compromised, the DUB01 hub & spoke is untouched. Resources are in dedicated subscriptions so the blast area of a subscription compromise is limited too.

There is also a logical placement of the resources based on ownership/location.

You don’t need to recreate policy – you can add more associations to your initiatives.

If an enterprise currently has a single networking team, their IDs are simply added to more groups as new hub & spoke deployments are added.

IP Planning

One of the key principles in the design is simplicity: keep it simple stupid (KISS). I’m going to jump ahead a little here and give you a peek into the future. We will implement “Network segmentation: Many ingress/egress cloud micro-perimeters with some micro-segmentation” from the Azure zero-trust guidance.

The only connection that will exist between DUB01 and AMS01 is a global VNet peering connection between the hubs. All traffic between DUB01 and AMS01 mist route via the firewalls in the hubs. This will require some user-defined routing and we want to keep this as simple as possible.

For example, the firewall subnet in DUB01 must have a route(s) to all prefixes in AMS01 via the firewall in the hub of AMS01. The more prefixes there are in AMS01, the more routes we must add to the Route Table associated with the firewall subnet in the hub of DUB01. So we will keep this very simple.

Each hub & spoke will be created from a single IP prefix allocation:

- DUB01: All virtual networks in DUB01 will be created from 10.1.0.0/16.

- AMS01: All virtual networks in AMS01 will be created from 10.2.0.0/16.

You might have noticed that Azure Virtual Network Manager uses a default of /16 for an IP address block in the IPAM feature – how convenient!

That means I only have to create one route in the DUB01 firewall subnet to reach all virtual networks in AMS01:

- Name: AMS01

- Prefix: 10.2.0.0/16

- Next Hop Type: VirtualAppliance

- Next Hop IP Address: The IP address of the AMS01 firewall

A similar route will be created in AMS01 firewall subnet to reach all virtual networks in DUB01:

- Name: DUB01

- Prefix: 10.1.0.0/16

- Next Hop Type: VirtualAppliance

- Next Hop IP Address: The IP address of the DUB01 firewall

Honestly, that is all that is required. I’ve been doing it for years. It’s beautifully simple.

The firewall(s) are in total control of the flows. This design means that neither location is dependent on the other. Neither AMS01 nor DUB01 trust each other. If a workload is compromised in AMS01 its reach is limited to whatever firewall/NSG rules permit traffic. With threat detection, flow logs, and other features, you might even discover an attack using a security information & event management (SIEM) system before it even has a chance to spread.

Workloads/Landing Zones

Every workload will have a dedicated subscription with the appropriate configurations, such as enabling budgets and configuring Defender for Cloud. Standards should be as automated as possible (Azure Policy). The exact configuration of the subscription should depend on the zone (corp, online or corporate).

When there is a virtual network requirement, then the virtual network will be as small as is required with some spare capacity. For example, a workload with a web VM and a SQL Server doesn’t need a /24 subnet!

Essential Workloads

Are you going to migrate legacy workloads to Azure? Are you going to run Citrix or Azure Virtual Desktop (AVD)? If so, then you are going to require doamin controllers.

You might say “We have a policy of running a single ADDS site and our domain controllers are on-premises”. Lovely, at least it was when Windows Server 2003 came out. Remember that I want my services in Azure to be resilient and not to depend on other locations. What happens to all of your Azure servces when the network connection to on-premises fails? Or what happens if on-premises goes up in a cloud of smoke? I will put domain controllers in Azure.

Then you might say “We will put domain controllers in DUB01 and AMS01 can use them”. What happens if DUB01 goes offline? That does happen from time to time. What happens if DUB01 is compromised? Not only will I put domain controllers in DUB01, but I will also put them in AMS01. They are low end virtual machines and the cost will be minor. I’ll also do some good ADDS Sites & Services stuff to isolate as much as ADDS lets you:

- Create subnets for each /16 IP prefix.

- Create an ADDS site for AMS01 and another for DUB01.

- Associate each site with the related subnet.

- Create and configure replication links as required.

The placement and resilience of other things like DNS servers/Private DNS Resolver should be similar.

And none of those things will go in the hub!

Micro-Segmentation

The hub will be our transit network, providing:

- Site-to-site connectivity, if required.

- Point-to-site connecticity, if required.

- A firewall for security and routing purposes.

- A shared Azure Bastion, if required.

The firewall will be the next hop, by default (expect exceptions) for traffic leaving every virtual network. This will be configured for every subnet (expect exceptions) in every workload.

The firewall will be the glue that routes every spoke virtual network to each other and the outside world. The firewall rules will restrict which of those routes is possible and what traffic is possible – in all directions. Don’t be lazy and allow * to Internet; do you want to automatically enable malware to call home for further downloads or discovery/attack/theft instructions?

The firewall will be carefully chosen to ensure that it includes the features that your organisation requires. Too many organisations pick the cheapest firewall option. Few look at the genuine risks that they face and pick something that best defends against those risks. Allow/deny is not enough any more. Consider the features that pay careful attentiont to what must be allowed; these are the firewall ports that attackers are using to compromise their victims.

Every subnet (expect exceptions) will have an NSG. That NSG will have a custom low-priority inbound rule to deny everything; this means that no traffic can enter a NIC (from anywhere, including the same subnet) without being explicityly allowed by a higher priority rule.

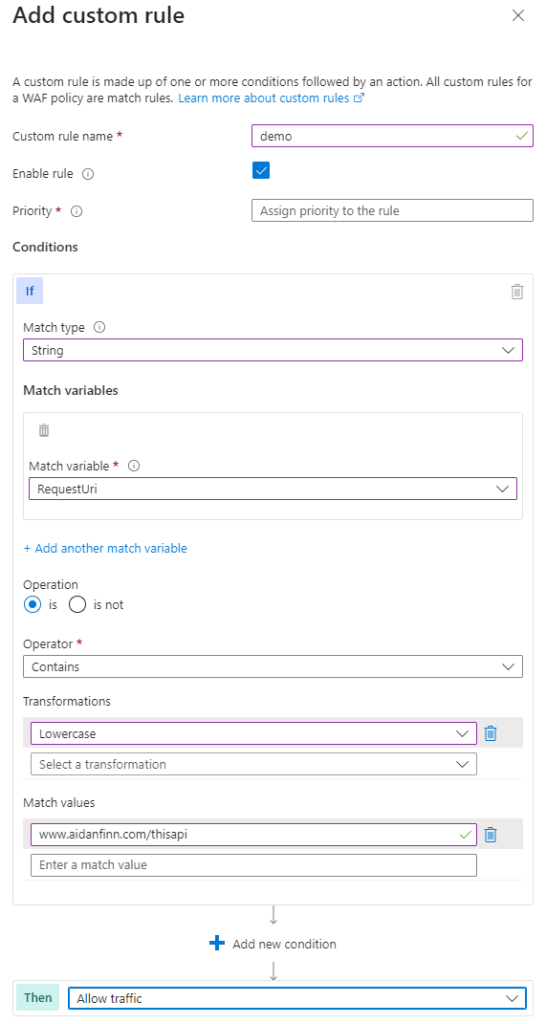

“Web” (this covers a lot of HTTPS based services, excluding AVD) applications will not be published on the Internet using the hub firewall. Instead, you will deploy a WAF of some kind (or different kinds depending on architectural/business requirements). If you’re clever, and it is appropriate from a performance perspective, you might route that traffic through your firewall for inspection at layers 4-7 using TLS Inspection and IDPS.

Logging and Alerting

You have placed all the barriers in place. There are two interesting quotes to consider. The first warns us that we must assume a pentration has already taken place or will take place.

Fundamentally, if somebody wants to get in, they’re getting in…accept that. What we tell clients is: Number one, you’re in the fight, whether you thought you were or not. Number two, you almost certainly are penetrated.

Michael Hayden Former Director of NSA & CIA

The second warns us that attackers don’t think like defenders. We build walls expecting a linear attack. Attackers poke, explore, and prod, looking for any way, including very indeirect routes, to get from A to B.

Biggest problem with network defense is that defenders think in lists. Attackers think in graphs. As long as this is true, attackers win.

John Lambert

Each of our walls offers some kind of monitoring. The firewall has logs, which ideally we can either monitor/alert from or forward to a SIEM.

Virtual Networks offer Flow Logs which track traffic at the VNet level. VNet Flow logs are superior to NSG FLow logs because they catch more traffic (Private Endpoint) and include more interesting data. This is more data that we can send to a SIEM.

Defender for Cloud creates data/alerts. Key Vaults do. Azure databases do. The list goes on and on. All of this data that we can use to:

- Detect an attack

- Identify exploration

- Uncover an expansion

- Understand how an attack started and happened

And it amazes me how many organisations choose not to configure these features in any way at all.

Wrapping Up

There are probably lots of finer details to consider but I think that I have covered the essentials. When I get the chance, I’ll start diving into the fun detailed designs and their variations.