In this post, I’ll explain how Azure Virtual WAN offers its core service: connections.

SD-WAN

Some of you might be thinking – this is just for large corporations and I’m outta here. Don’t run just yet. Azure Virtual WAN is a rethinking of how to:

- Connect users to Azure services and on-premises at the same time

- Connect sites to Azure and (optionally) other sites

- Replace the legacy hardware-defined WAN

- Connect Azure virtual networks together.

That first point is quite timely – connecting users to services. Work-from-home (WFH) has forced enterprises to find ways to connect users to services no matter where they are. That connectivity was often limited to a privileged few. The pandemic forced small/large organisations to re-think productivity connectivity and to scale out. Before COVID19 struck, I was starting to encounter businesses that were considering (some even starting) to replace their legacy MPLS WAN with a software-defined WAN (SD-WAN) where media of different types, suitable to different kinds of sites/users/services, were aggregated via appliances; this SD-WAN is lower cost, more flexible, and by leveraging local connectivity, enables smaller locations, such as offices or retail outlets, to have an affordable direct connection to the cloud for better performance. How the on-premises part of the SD-WAN is managed is completely up to you; some will take direct control and some will outsource it to a network service provider.

Connections

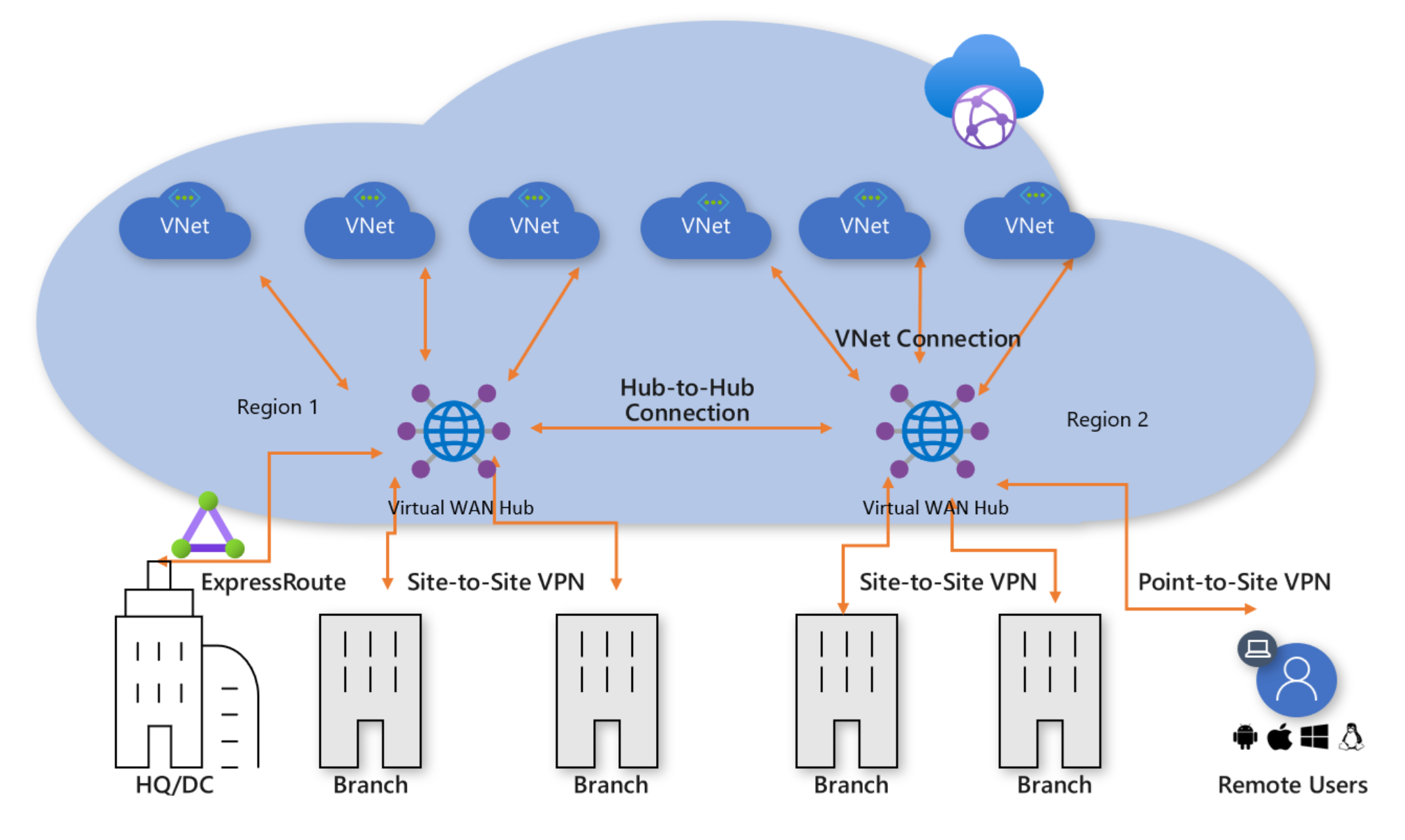

Azure Virtual WAN is all about connections. When you start to read about the new Custom Routing model in Azure Virtual WAN, you’ll see how route tables are associated with connections. In summary, a connection is a link between an on-premises location (referred to as a branch, even if it’s HQ) or a spoke virtual network with a Hub. And now we need to talk about some Azure resources.

Azure Resources

I’ve provided lots more depth on this topic elsewhere so I will keep this to the basics. There are two core resources in Azure Virtual WAN:

The Virtual WAN is a logical resource that provides a global service, although it is actually located in one Azure region. Any hubs that are connected to this Virtual WAN resource can talk to each other (automatically), route it’s connections to another hub’s connections and share resources.

A Virtual WAN Hub is similar to a hub in an Azure hub & spoke architecture. It is a central routing point (with a hidden virtual router) that is the meeting point for any connections to that hub. An Azure region can have 1 hub in your tenant. That means I can have 1 Hub in West Europe and 1 Hub in East US. The Hubs must be connected to an Azure WAN resource; if they share a WAN resource then their connections can talk to each other. I might have all my branches in Europe connect to the Hub in West Europe, and I will connect all my spoke virtual networks in West Europe to the Hub in West Europe too; this means that by default (and I can control this):

- The virtual networks can route to each other

- The virtual networks can route to the branches

- The branches can route to the virtual networks

- The branches can route to other branches

We can extend this routing by connecting my branches in North America to the East US Hub and the spoke virtual networks in East US to the East US Hub. Yes; all those North American locations can route to each other. Because the Hubs are connected to a common Virtual WAN, the routing now extends across the Microsoft WAN. That means a retail outlet in the further reaches of northwest rural Ireland can connect to services hosted in East US, via a connection to the Hub in West Europe, and then hopping across the Atlantic Ocean using Microsoft’s low-latency WAN. Nice, right? Even, better – it routes just like that automatically if you are using SD-WAN appliances in the branches.

Note that a managed WAN might wire up that retail outlet differently, but still provide a fairly low-latency connection to the local Hub.

Branch Connections

If you have done any Azure networking then you are probably familiar with:

- Site-to-site VPN: Connecting a location with a cost-effective but no-SLA VPN tunnel to Azure.

- ExpressRoute: A circuit rented from an ISP for low-latency, high bandwidth, and an SLA-supported private connection to Azure

- Point-to-Site VPN: Enabling end-users to create a private VPN tunnel to Azure from their devices while on the move or working from home

Each of the above is enabled in Azure using a Virtual Network Gateway, each running independently. Routing from branch to branch is not an intended purpose. Routing from user to the branch is not an intended purpose. The Virtual Network Gateway’s job is to connect a user to Azure.

The Azure Virtual WAN Hub supports gateways – as hidden resources that must be enabled and configured. All three of the above media types are supported as 3 different types of gateway, sized based on a billing concept called scale units – more scale units means more bandwidth and more cost, with a maximum hub throughput of 40 Gbps (including traffic to/from/between spokes).

Note that a Secured Virtual Hub, featuring the Azure Firewall, has a limit of 30 Gbps if all traffic is routed through that firewall.

You can be flexible with the branch connections. Some locations might be small and have a VPN connection to the Hub. Other locations might require an SLA and use ExpressRoute. Some might require low latency or greater bandwidth and use higher SKUs of ExpressRoute. And of course, some users will be on the move or at home and use P2S VPN. A combination of all 3 connection types can be used at once, providing each location and user the connections and costs that suit them best.

ExpressRoute

You will be using ExpressRoute Standard for Azure Virtual WAN; this is a requirement. I don’t think there’s really too much more to say here – the tech just works once the circuit is up, and a combination of Global Reach and the any-to-any connections/routing of Azure WAN means that things will just work.

Site-to-Site VPN

The VPN gateway is deployed in an active/active cluster configuration with two public IP addresses. A branch using VPN for connectivity can have:

- A single VPN connection over a single ISP connection.

- Resilient VPN connections over two ISP connections, ideally with different physical providers or even media types.

An on-premises SD-WAN appliance is strongly recommended for Azure Virtual WAN, but you can use any VPN appliance that is supported for route-based VPN by Microsoft Azure; if you are doing the latter you can use BGP or the Azure WAN alternative to Local Network Gateway-provided prefixes for routing to on-premises.

Point-to-Site (P2S) VPN

The P2S gateway offers a superior service to what you might have observed with the traditional Virtual Network Gateway for VPN. Connectivity from the user device is to a hub with a routing appliance. Any-to-any connectivity treats the user device as a branch, albeit in a dedicated network address space. Once the user has connected the VPN tunnel, they can route to (by default):

- Any spoke virtual network connected to the Hub

- Any spoke virtual network connected to another Hub on the same Virtual WAN

- Any branch office connected to any Hub on the Virtual WAN

In summary, the user is connected to the WAN as a result of being connected to the Hub and is subject to the routing and firewall configurations of that Hub. That’s a pretty nice WFH connectivity solution.

Note that you have support for certificate and RADIUS authentication in P2S VPN, as well as the OpenVPN and Microsoft client.

The Connectivity Experience

Imagine we’re back in normal times again with common business travel. A user in Amsterdam could sit down at their desk in the office and connect to services in West Europe via VPN. They could travel to a small office in Luxembourg and connect to the same services via VPN with no discernible difference. That user could travel to a conference in London and use P2S VPN from their hotel room to connect via the Amsterdam Hub. Now that user might get a jet to Philadelphia, and use their mobile hotspot to offer connectivity to the Azure Virtual WAN Hub in East US via P2S VPN – and the experience is no different!

One concept I would like to try out and get a support statement on is to abstract the IP addresses and locations of the P2S gateways using Azure Traffic Manager so the user only needs to VPN to a single FQDN and is directed (using the performance profile) to the closest (latency) Hub in the Virtual WAN with a P2S gateway.

Simplicity

So much is done for you with Azure Virtual WAN. If you like to click in the Azure Portal, it’s a pretty simple set up to get things going, although security engineering looks to have a steep learning curve with Custom Routing. By default, everything is connected to everything; that’s what a network should do. You shouldn’t have to figure out how to route from A to B. I believe that Azure WAN will offer a superior connectivity solution, even for a single location organisation. That’s why I’ve been spending time figuring this tech out over the last few weeks.