This post about Azure Virtual Network Manager is a part of the online community event, Azure Back To School 2024. In this post, I will discuss how you can use Azure Virtual Network Manager (AVNM) to centrally manage large numbers of Azure virtual networks in a rapidly changing/agile and/or static environment.

Challenges

Organisations around the globe have a common experience: dealing with a large number of networks that rapidly appear/disappear is very hard. If those networks are centrally managed then there is a lot of re-work. If the networks are managed by developers/operators then there is a lot of governance/verification work.

You need to ensure that networks are connected and are routed according to organisation requirements. Mandatory security rules must be put in place to either allow required traffic or to block undesired flows.

That wasn’t a big deal in the old days when there were maybe 3-4 huge overly trusting subnets in the data centre. Network designs change when we take advantage of the ability to transform when deploying to the cloud; we break those networks down into much smaller Azure virtual networks and implement micro-segmentation. This approach introduces simplified governance and a superior security model that can reliably build barriers to advanced persistent threats. Things sound better until you realise that there are no many more networks and subnets that there ever were in the on-premises data centre, and each one requires management.

This is what Azure Virtual Network Manager was created to help with.

Introducing Azure Virtual Network Manager

AVNM is not a new product but it has not gained a lot of traction yet – I’ll get into that a little later. Spoiler alert: things might be changing!

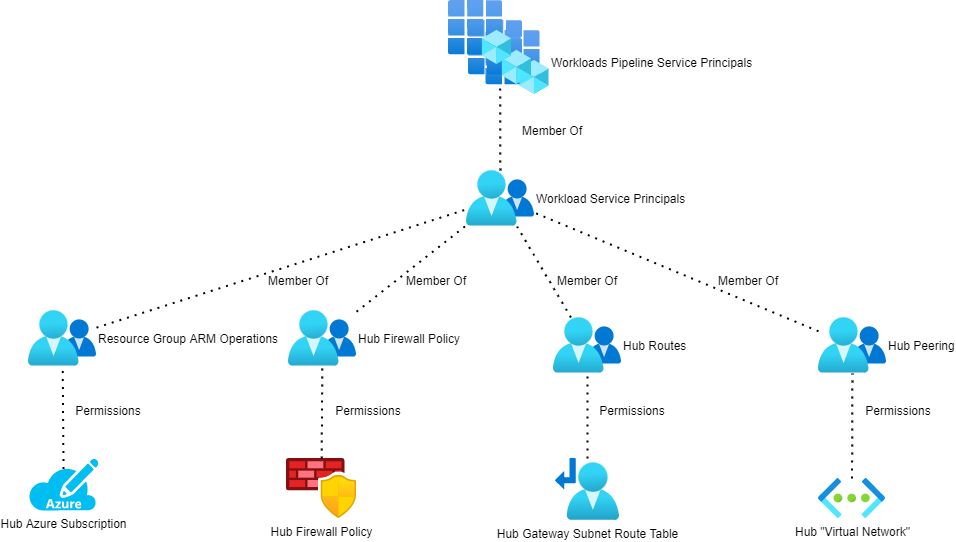

The purpose of AVNM is to centralise configuration of Azure virtual networks and to introduce some level of governance. Don’t get me wrong, AVNM does not replace Azure Policy. In fact, AVNM uses Azure Policy to do some of the leg work. The concept is to bring a network-specialist toolset to the centralised control of networks instead of using a generic toolset (Azure Policy) that can be … how do I say this politely … hmm … mysterious and a complete pain in the you-know-what to troubleshoot.

AVNM has a growing set of features to assist us:

- Network groups: A way to identify virtual networks or subnets that we want to manage.

- Connectivity configurations: Manage how multiple virtual networks are connected.

- Security admin rules: Enforce security rules at the point of subnet connection (the NIC).

- Routing configurations: Deploy user-defined routes by policy.

- Verifier: Verify the networks can allow required flows.

Deployment Methodology

The approach is pretty simple:

- Identify a collection of networks/subnets you want to configure by creating a Network Group.

- Build a configuration, such as connectivity, security admin rules, or routing.

- Deploy the configuration targeting a Network Group and one or more Azure regions.

The configuration you build will be deployed to the network group members in the selected region(s).

Network Groups

Part of a scalable configuration feature of AVNM is network groups. You will probably build several or many network groups, each collecting a set of subnets or networks that have some common configuration requirement. This means that you can have ea large collection of targets for one configuration deployment.

Network Groups can be:

- Static: You manually add specific networks to the group. This is ideal for a limited and (normally) unchanging set of targets to receive a configuration.

- Dynamic: You will define a query based on one or more parameters to automatically discover current and future networks. The underlying mechanism that is used for this discovery is Azure Policy – the query is created as a policy and assigned to the scope of the query.

Dynamic groups are what you should end up using most of the time. For example, in a governed environment, Azure resources are often tagged. One can query virtual networks with specific tags and in specific Azure regions and have them automatically appear in a network group. If a developer/operator creates a new network, governance will kick in and tag those networks. Azure Policy will discover the networks and instantly inform AVNM that a new group member was discovered – any configurations applied to the group will be immediately deployed to the new network. That sounds pretty nice, right?

Connectivity Configurations

Before we continue, I want you to understand that virtual network peering is not some magical line or pipe. It’s simply an instruction to the Azure network fabric to say “A collection of NICs A can now talk with a collection of NICs B”.

We often want to either simplify the connectivity of networks or to automate desired connectivity. Doing this at scale can be done using code, but doing it in an agile environment requires trust. Failure usually happens between the chair and the keyboard, so we want to automate desired connectivity, especially when that connectivity enables integration or plays a role in security/compliance.

Connectivity Configurations enable three types of network architecture:

- Hub-and-spoke: This is the most common design I see being required and the only one I’ve ever implemented for mid-large clients. A central regional hub is deployed for security/transit. Workloads/data are placed in spokes and are peered only with the hub (the network core). A router/firewall is normally (not always) the next hop to leave a spoke.

- Full mesh: Every virtual network is connected directly to every other virtual network.

- Hub-and-spoke with mesh: All spokes are connected to the hub. All spokes are connected to each other. Traffic to/from the outside world must go through the hub. Traffic to other spokes goes directly to the destination.

Mesh is interesting. Why would one use it? Normally one would not – a firewall in the hub is a desirable thing to implement micro-segmentation and advanced security features such as Intrusion Detection and Prevention System (IDPS). But there are business requirements that can override security for limited scenarios. Imagine you have a collection of systems that must integrate with minimised latency. If you force a hop through a firewall then latency will potentially be doubled. If that firewall is deemed an unnecessary security barrier for these limited integrations by the business, then this is a scenario where a full mesh can play a role.

This is why I started off discussing peering. Whether a system is in the same subnet/network or not, it doesn’t matter. The physical distance matters, not the virtual distance. Peering is not a cable or a connection – it’s just an instruction.

However, Virtual Network Peering is not even used in mesh! It’s something different that can handle the scale of many virtual networks being interconnected called a Connected Group. One configuration inter-connects all the virtual networks without having to create 1-1 peerings between many virtual networks.

A very nice option with this configuration is the ability to automatically remove pre-existing peering connections to clean up unwanted previous designs.

Security Admin Rules

What is a Network Security Group (NSG) rule? It’s a Hyper-V port ACL that is implemented at the NIC of the virtual machine (yours or in the platform hosting your PaaS service). The subnet or NIC association is simply a scaling/targeting system; the rules are always implemented at the NIC where the virtual switch port is located.

NSGs do not scale well. Imagine you need to deploy a rule to all subnets/NICs to allow/block a flow. How many edits will you need to do? And how much time will you waste on prioritising rules to ensure that your rule is processed first?

Security Admin Rules are also implemented using Port ACLs but they are always processed first. You can create a rule or a set or rules and deploy it to a Network Group. All NICs will be updated and your rules will always be processed first.

Tip: Consider using VNet Flow Logs to troubleshoot Security Admin Rules.

Routing Configurations

This is one of the newer features in AVNM and was a technical blocker for me until it was introduced. Routing plays a huge role in a security design, forcing traffic from the spoke through a firewall in the hub. Typically, in VNet-based hub deployments, we place one user-defined route (UDR) in each subnet to make that flow happen. That doesn’t scale well and relies on trust. Some have considered using BGP routing to accomplish this but that can be easily overridden after quite a bit of effort/cost to get the route propagated in the first place.

AVNM introduced a preview to centrally configure UDRs and deploy them to Network Groups with just a few clicks. There are a few variations on this concept to decide how granular you want the resulting Route Tables to be:

- One is shared with virtual networks.

- One is shared with all subnets in a virtual network.

- One per subnet.

Verification

This is a feature that I’m a little puzzled about and I am left wondering if it will play a role in some other future feature. The idea is that you can test your configurations to ensure that they are working. There is a LOT of cross-over with Network Watcher and there is a common limitation: it only works with virtual machines.

What’s The Bad News?

Once routing configurations go generally available, I would want to use AVNM in every deployment that I do in the future. But there is a major blocker: pricing. AVNM is priced per subscription at $73/month. For those of you with a handful of subscriptions, that’s not much at all. But for those of us who saw that the subscription is a natural governance boundary and use LOTS of subscriptions (like in Microsoft Cloud Adoption Framework), this is a huge deal – it can make AVNM the most expensive thing we do in Azure!

The good news is that the message has gotten through to Microsoft and some folks in Azure networking have publicly commented that they are considering changes to the way that the pricing of AVNM is calculated.

The other bit bad news is an oldie: Azure Policy. Dynamic network group membership is built by Azure Policy. If a new virtual network is created by a developer, it can be hours before policy detects it and informs AVNM. In my testing, I’ve verified that once AVNM sees the new member, it triggers the deployment immediately, but the use of Azure Policy does create latency, enabling some bad practices to be implemented in the meantime.

Summary

I was a downer on AVNM early on. But recent developments and some of the ideas that the team is working on have won me over. The only real blocker is pricing, but I think that the team is serious about fixing that. I stated earlier that AVNM hasn’t gotten a lot of traction. I think that this should change once pricing is fixed and routing configurations are GA.

I recently demonstrated using AVNM to build out the connectivity and routing of a hub-and-spoke with micro-segmentation at a conference. Using Azure Portal, the entire configuration probably took less than 10 minutes. Imagine that: 10 minutes to build out your security and compliance model for now and for the future.