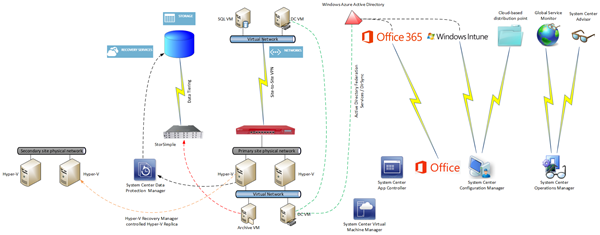

I am attempting to map out the infrastructure elements (not the app/dev elements) of the Microsoft hybrid cloud. This is a work in progress. If you spot any missing pieces then please comment and I will update.

You’ve heard terms like Cloud OS and hybrid cloud. What do they mean? I will attempt to map out the Microsoft hybrid cloud’s infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) ans software-as-a-service (SaaS) elements in this post.

The Hybrid Cloud

A private cloud is a single-tenant (but many users) service that is typically run on-premise. Note that there is a concept of a hosted private cloud; this is where a hosting company runs your single tenant infrastructure. An example of a private cloud is Hyper-V with elements of System Center (VMM, App Controller, Windows Azure Pack, etc) running in your data centre.

A public cloud is a hosted multi-tenant service that you do not own, but you consume services from. The perfect examples of this are Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Microsoft Windows Azure. The hosting company runs and hides the infrastructure from you. You subscribe to services from this shared infrastructure and have no visibility of other tenants. Those offerings are IaaS. There is platform-as-a-service (PaaS) which Windows Azure also offers for developers to run their applications without worrying about VM guest operating systems. And there is software-as-a-service (SaaS) such as Office 365 and Windows Intune where you use some software that the hosting company runs and sells to you from the cloud.

A hybrid cloud is where you mix elements of private cloud with public cloud. Microsoft is in a very unique position because they operate/sell IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS in public and private cloud. This allows you to integrate the best elements (for you) of on-premise with the public cloud offerings of Microsoft to create a hybrid offering.

The Map

View the image to see full size

View the image to see full size

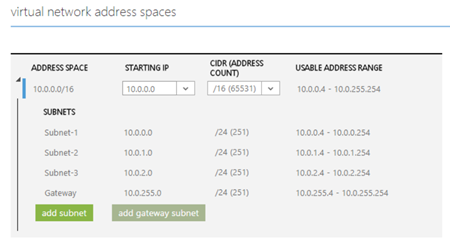

Windows Azure Site-Site VPN

You can deploy virtual machines in Windows Azure. They are very similar to Hyper-V VMs, because at this point, Windows Azure is running WS2012 Hyper-V (not WS2012 R2, as you can tell by digging around). You can deploy Software-Defined-Networking (SDN) within Windows Azure in the form of Virtual Networks; you define a network and then you define automatically routed subnets. You can configure a remote gateway to enable site-to-site VPN connectivity between your on-premise infrastructure and the network within Windows Azure. That creates intriguing possibilities where you run some services within Windows Azure to take advantage of elasticity and instant resource availability, and take advantage of on-premise where you can customise and specialise to your heart’s content.

An MPLS alternative has gone into beta with AT&T in the USA. Basically the Windows Azure network becomes another branch office on your WAN. That would be a much nicer and more fault tolerant option than single site-to-site VPN.

Note:

You will use SCVMM to manage your on-premise cloud(s) and use System Center App Controller to enable easy deployment of VMs/services in your hybrid cloud.

Active Directory

One of the biggest historical pains in IT for users is having multiple usernames and passwords. You can have single-sign-on (SSO) across your on-premise and Microsoft public cloud services by synchronising Active Directory with Windows Azure Active Directory (WAAD). WAAD is used in a couple of ways:

- PaaS: Developers can use synchronised IDs for their custom applications.

-

SaaS: Office 365 (Midsize [M] plan and up) and Windows Intune can use the same user names for Exchange Online, SharePoint Online, Lync Online, etc, as are entered when users sign into their PC every day.

There are two ways to synchronise AD with WAAD:

- DirSync: Is a simple-to-install and manage solution for smaller businesses.

- ADFS: Active Directory Federation Services is used for larger installs. It requires HA because ADFS becomes a point of dependency to sign into services.

Another interesting option is to deploy VMs into Windows Azure, promote one or more to be domain controllers, and treat that as another site in your Active Directory forest. Your on-premise DCs will replicate with the DCs running in Windows Azure. This is used to enable traditional user & computer join/login to your AD forest.

Note: You must follow specific guidelines for creating DCs in Windows Azure. For example, all domain databases must be placed on an additional data drive that you attach to the VM. This is required to avoid corruption.

Office 365

I’ve already mentioned how users can sign into Office 365 (M plan and higher) using the same username and password as they use on their PC. You can also run hybrid Office services. For example, an Exchange organisation can span on-premise Exchange servers and the cloud.

Windows Intune & System Center Configuration Manager

System Center Configuration Manager (SCCM) is Microsoft’s corporate device deployment & management solution. I believe it is best used when limited to direct management of domain-joined Windows computers. Note that SCCM does allow you to deploy a distribution point (a content library that users/computers install from) in the cloud (hosted by Windows Azure).

You can also get Windows Intune, Microsoft’s cloud-based device management solution. Being cloud based makes it easy to deploy, and better for managing remote or widely distributed devices. Intune is less AD-centric, and that also makes it a great product for dealing with bring-your-own-device (BYOD). And Intune is also designed from the ground up to manage non-Windows OSs such as Android, iOS, and Windows Phone.

You can integrate Windows Intune into SCCM so admins have a single console to manage. I see Intune as the mechanism for dealing with widely distributed devices, roaming devices, mobile devices, and BYOD. SCCM is the solution for dealing with domain-joined corporate computers.

System Center Operations Manager

SCOM is Microsoft’s service-focused monitoring solution. You can get lots of Microsoft developed (free) management packs for monitoring on-premise stuff such as Windows Server, AD, SQL Server, and much more. There are also free third-party management packs (HP, Dell, Citrix, and more), and paid-for products from the likes of Veeam (which happens to have a limited free package for vSphere monitoring).

SCOM can also be used with the cloud in a few ways:

- Global Service Monitor: GSM allows you to monitor the availability and quality of web services from Microsoft’s data centres around the world. This accounts for the fact that the Internet is complex and localised failures can affect international service availability in unpredictable ways. You configure GSM to monitor site(s) and the results appear in SCOM.

- System Center Advisor: Think of this as a best practices analyzer from the cloud. SCOM can monitor the results of Advisor scans.

- Windows Azure: You can monitor the services that you deploy in Azure in two ways. You can monitor the Azure service itself for failures. You can also install SCOM agents into the guest OS of your VMs to monitor the OS and services from within the VMs.

StorSimple

Many businesses struggle with retaining archive data. Microsoft acquired StorSimple to deal with that issue. This is a on-premise installed 1 GbE iSCSI storage appliance that offers local SSD and HDD tiers with a third colder tier residing within the storage services of Windows Azure.

The appliance is not suitable for all workloads. A key requirement is that your data must have a concept of a “working set”. In other words, there is hot data that you use frequently, and cold data that your do not look at very often. VM VHD/VHDX files are not examples of this. Think of a corporate file server, an CAD library, etc. Those are good examples.

StorSimple also has a built-in backup system that uses snapshot mechanisms to backup your hot/cold data.

Windows Azure Online Backup

There are many ways to use the storage mechanisms in Azure. Another one is to use Online Backup to automate the off-site storage of your backup data. A basic system for a single server would be to let Windows Server Backup send its data directly to the cloud. Larger customers might use something like System Center Data Protection Manager or Commvault Sympana to send their backup data to Windows Azure.

The data is encrypted using your private key. Microsoft never sees this key, and therefore you must keep the key safe; they cannot rescue you if you lose it.

I’ve been told that there is a beta in the USA to assist with getting that first big backup into the data center using secure out of band couriers. This will be a much more complex service to export due to the nature of international cross-border complexities.

Hyper-V Recovery Manager

HRM is not a solution that I am convinced about, due to pricing and the fact that it lives in Azure. I prefer micro-payment and placement in the secondary site.

However, HRM is an orchestration solution that lives in Windows Azure for coordinating Hyper-V Replica between two VMM-managed Hyper-V sites. Asynchronous replication data flows directly between the two sites, never to Azure. HRM purely manages replication and failover.

SQL Server 2014

SQL Server AlwaysOn availability groups can span on-premise and in-Azure VMs, enabling hybrid cloud HA of your relational data services.