In this post, I will show how to use Azure Virtual Network Manager (AVNM) to enforce peering and routing policies in a zero-trust hub-and-spoke Azure network. The goal will be to deliver ongoing consistency of the connectivity and security model, reduce operational friction, and ensure standardisation over time.

Quick Overview

AVNM is a tool that has been evolving and continues to evolve from something that I considered overpriced and under-featured, to something that I would want to deploy first in my networking architecture with its recently updated pricing. In summary, AVNM offers:

- Network/subnet discovery and grouping

- IP Address Management (IPAM)

- Connectivity automation

- Routing automation

There is (and will be) more to AVNM, but I want to focus on the above features because together they simplify the task of building out Azure platform and application landing zones.

The Environment

One can manage virtual networks using static groups but that ignores the fact that The Cloud is a dynamic and agile place. Developers, operators, and (other) service providers will be deploying virtual networks. Our goal will be to discover and manage those networks. An organisation might be simple, and there will be a one-size-fits-all policy. However, we might need to engineer for complexity. We can reduce that complexity by organising:

- Adopt the Cloud Adoption Framework and Zero Trust recommendations of 1 subscription/virtual network per workload.

- Organising subscriptions (workloads) using Management Groups.

- Designing a Management Group hierarchy based on policy/RBAC inheritance instead of basing it on an organisation chart.

- Using tags to denote roles for virtual networks.

I have built a demo lab where I am creating a hub & spoke in the form of a virtual data centre (an old term used by Microsoft). This concept will use a hub to connect and segment workloads in an Azure region. Based on Route Table limitations, the hub will support up to 400 networked workloads placed in spoke virtual networks. The spokes will be peered to the hub.

A Management Group has been created for dub01. All subscriptions for the hub and workloads in the dub01 environment will be placed into the dub01 Management Group.

Each workload will be classified based on security, compliance, and any other requirements that the organisation may have. Three policies have been predefined and named gold, silver, and bronze. Each of these classifications has a Management Group inside dub01, called dub01gold, dub01silver, and dub01bronze. Workloads are placed into the appropriate Management Group based on their classification and are subject to Azure Policy initiatives that are assigned to dub01 (regional policies) and to the classification Management Groups.

You can see two subscriptions above. The platform landing zone, p-dub01, is going to be the hub for the network architecture. It has therefore been classified as gold. The workload (application landing zone) called p-demo01 has been classified as silver and is placed in the appropriate Management Group. Both gold and silver workloads should be networked and use private networking only where possible, meaning that p-demo01 will have a spoke virtual network for its resources. Spoke virtual networks in dub01 will be connected to the hub virtual network in p-dub01.

Keep in mind that no virtual networks exist at this time.

AVNM Resource

AVNM is based on an Azure resource and subresources for the features/configurations. The AVNM resource is deployed with a management scope; this means that a single AVNM resource can be created to manage a certain scope of virtual networks. One can centrally manage all virtual networks. Or one can create many AVNM resources to delegate management (and the cost) of managing various sets of virtual networks.

I’m going to keep this simple and use one AVNM resource as most organisations that aren’t huge will do. I will place the AVNM resource in a subscription at the top of my Management Group hierarchy so that it can offer centralised management of many hub-and-spoke deployments, even if we only plan to have 1 now; plans change! This also allows me to have specialised RBAC for managing AVNM.

Note that AVNM can manage virtual networks across many regions so my AVNM resource will, for demonstration purposes, be in West Europe while my hub and spoke will be in North Europe. I have enabled the Connectivity, Security Admin, and User-Defined Routing features.

AVNM has one or more management scopes. This is a central AVNM for all networks, so I’m setting the Tenant Root Group as the top of the scope. In a lab, you might use a single subscription or a dedicated Management Group.

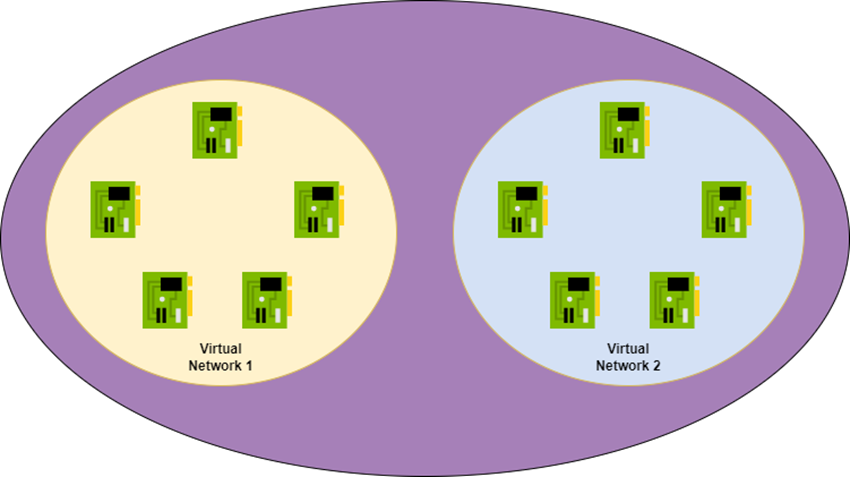

Defining Network Groups

We use Network Groups to assign a single configuration to many virtual networks at once. There are two kinds of members:

- Static: You add/remove members to or from the group

- Dynamic: You use a friendly wizard to define an Azure Policy to automatically find virtual networks and add/remove them for you. Keep in mind that Azure Policy might take a while to discover virtual networks because of how irregularly it runs. However, once added, the configuration deployment is immediately triggered by AVNM.

There are two kinds of members in a group:

- Virtual networks: The virtual network and contained subnets are subject to the policy. Virtual networks may be static or dynamic members.

- Subnets: Only the subnet is targeted by the configuration. Subnets are only static members.

Keep in mind that something like peering only targets a virtual network and User-Defined Routes target subnets.

I want to create a group to target all virtual networks in the dub01 scope. This group will be the basis for configuring any virtual network (except the hub) to be a secured spoke virtual network.

I created a Network Group called dub01spokes with a member type of Virtual Networks.

I then opened the Network Group and configured dynamic membership using this Azure Policy editor:

Any discovered virtual network that is not in the p-dub01 subscription and is in North Europe will be automatically added to this group.

The resulting policy is visible in Azure Policy with a category of Azure Virtual Network Manager.

IP Address Management

I’ve been using an approach of assigning a /16 to all virtual networks in a hub & spoke for years. This approach blocks the prefix in the organisation and guarantees IP capacity for all workloads in the future. It also simplifies routing and firewall rules. For example, a single route will be needed in other hubs if we need to interconnect multiple hub-and-spoke deployments.

I can reserve this capacity in AVNM IP Address Management. You can see that I have reserved 10.1.0.0/16 for dub01:

Every virtual network in dub01 will be created from this pool.

Creating The Hub Virtual Network

I’m going to save some time/money here by creating a skeleton hub. I won’t deploy a route NVA/Virtual Network Gateway so I won’t be able to share it later. I also won’t deploy a firewall, but the private address of the firewall will be 10.1.0.4.

I’m going to deploy a virtual network to use as the hub. I can use Bicep, Terraform, PowerShell, AZ CLI, or the Azure Portal. The important thing is that I refer to the IP address pool (above) when assigning an address prefix to the new virtual network. A check box called Allocate Using IP Address Pools opens a blade in the Azure Portal. Here you can select the Address Pool to take a prefix from for the new virtual network. All I have to do is select the pool and then use a subnet mask to decide how many addresses to take from the pool (/22 for my hub).

Note that the only time that I’ve had to ask a human for an address was when I created the pool. I can create virtual networks with non-conflicting addresses without any friction.

Create Connectivity Configuration

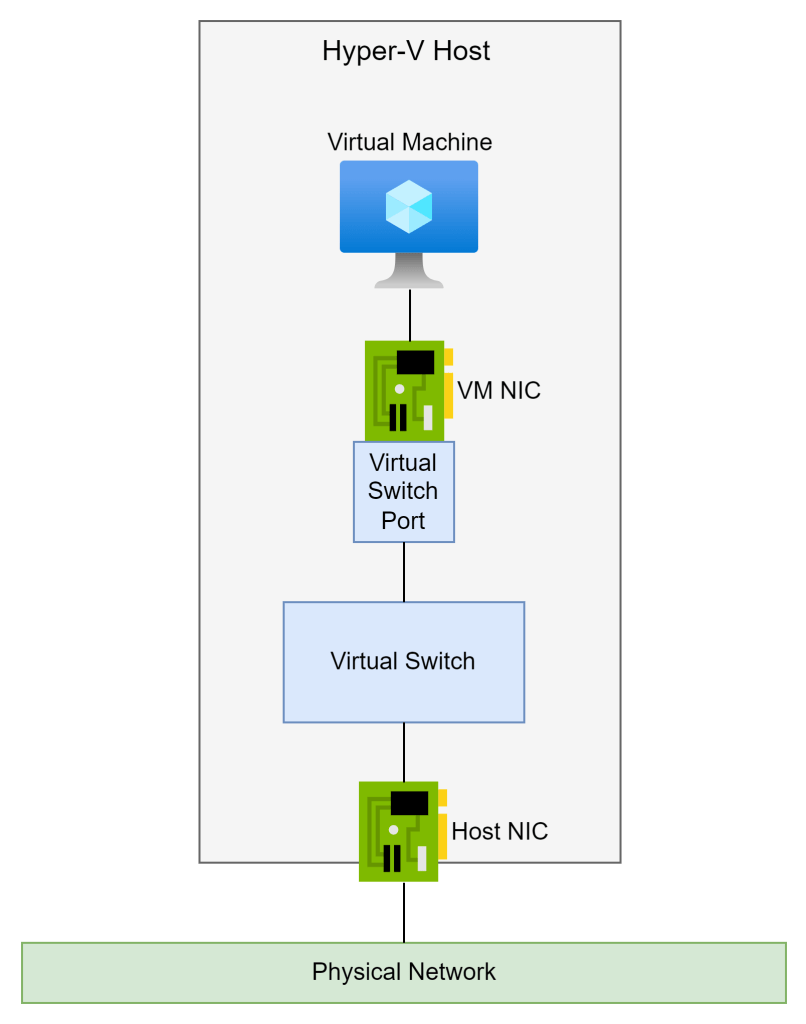

A Connectivity Configuration is a method of connecting virtual networks. We can implement:

- Hub-spoke peering: A traditional peering between a hub and a spoke, where the spoke can use the Virtual Network Gateway/Azure Route Server in the hub.

- Mesh: A mesh using a Connected Group (full mesh peering between all virtual networks). This is used to minimise latency between workloads with the understanding that a hub firewall will not have the opportunity to do deep inspection (performance over security).

- Hub & spoke with mesh: The targeted VNets are meshed together for interconnectivity. They will route through the hub to communicate with the outside world.

I will create a Connectivity Configuration for a traditional hub-and-spoke network. This means that:

- I don’t need to add code for VNet peering to my future templates.

- No matter who deploys a VNet in the scope of dub01, they will get peered with the hub. My design will be implemented, regardless of their knowledge or their willingness to comply with the organisation’s policies.

I created a new Connectivity Configuration called dub01spokepeering.

In Topology I set the type to hub-and-spoke. I select my hub virtual network from the p-dub01 subscription as the hub Virtual Network. I then select my group of networks that I want to peer with the hub by selecting the dub01spokes group. I can configure the peering connections; here I should select Hub As Gateway – I don’t have a Virtual Network Gateway or an Azure Route Server in the hub, so the box is greyed out.

I am not enabling inter-spoke connectivity using the above configuration – AVNM has a few tricks, and this is one of them, where it uses Connected Groups to create a mesh of peering in the fabric. Instead, I will be using routing (later) via a hub firewall for secure transitive connectivity, so I leave Enable Connectivity Within Network Group blank.

Did you notice the checkbox to delete any pre-existing peering configurations? If it isn’t peered to the hub then I’m removing it so nobody uses their rights to bypass by networking design.

I completed the wizard and executed the deployment against the North Europe region. I know that there is nothing to configure, but this “cleans up” the GUI.

Create Routing Configuration

Folks who have heard me discuss network security in Azure should have learned that the most important part of running a firewall in Azure is routing. We will configure routing in the spokes using AVNM. The hub firewall subnet(s) will have full knowledge of all other networks by design:

- Spokes: Using system routes generated by peering.

- Remote networks: Using BGP routes. The VPN Local Network Gateway creates BGP routes in the Azure Virtual Networks for “static routes” when BGP is not used in VPN tunnels. Azure Route Server will peer with NVA routers (SD-WAN, for example) to propagate remote site prefixes using BGP into the Azure Virtual Networks.

The spokes routing design is simple:

- A Route Table will be created for each subnet in the spoke Virtual Networks. This design for these free resources will allow customised routing for specific scenarios, such as VNet-integrated PaaS resources that require dedicated routes.

- A single User-Defined Route (UDR) forces traffic leaving a spoke Virtual Network to pass through the hub firewall, where firewall rules will deny all traffic by default.

- Traffic inside the Virtual Network will flow by default (directly from source to destination) and be subject to NSG rules, depending on support by the source and destination resource types.

- The spoke subnets will be configured not to accept BGP routes from the hub; this is to prevent the spoke from bypassing the hub firewall when routing to remote sites via the Virtual Network Gateway/NVA.

I created a Routing Configuration called dub01spokerouting. In this Routing Configuration I created a Rule Collection called dub01spokeroutingrules.

A User-Defined Route, known as a Routing Rule, was created called everywhere:

The new UDR will override (deactivate) the System route to 0.0.0.0/0 via Internet and set the hub firewall as the new default next hop for traffic leaving the Virtual Network.

Here you can see the Routing Collection containing the Routing Rule:

Note that Enable BGP Route Propagation is left unchecked and that I have selected dub01spokes as my target.

And here you can see the new Routing Configuration:

Completed Configurations

I now have two configurations completed and configured:

- The Connectivity Configuration will automatically peer in-scope Virtual Networks with the hub in p-dub01.

- The Routing Configuration will automatically configure routing for in-scope Virtual Network subnets to use the p-dub01 firewall as the next hop.

Guess what? We have just created a Zero Trust network! All that’s left is to set up spokes with their NSGs and a WAF/WAFs for HTTPS workloads.

Deploy Spoke Virtual Networks

We will create spoke Virtual Networks from the IPAM block just like we did with the hub. Here’s where the magic is going to happen.

The evaluation-style Azure Policy assignments that are created by AVNM will run approximately every 30 minutes. That means a new Virtual Network won’t be discovered straight after creation – but they will be discovered not long after. A signal will be sent to AVNM to update group memberships based on added or removed Virtual Networks, depending on the scope of each group’s Azure Policy. Configurations will be deployed or removed immediately after a Virtual Network is added or removed from the group.

To demonstrate this, I created a new spoke Virtual Network in p-demo01. I created a new Virtual Network called p-demo01-net-vnet in the resource group p-demo01-net:

You can see that I used the IPAM address block to get a unique address space from the dub01 /16 prefix. I added a subnet called CommonSubnet with a /28 prefix. What you don’t see is that I configured the following for the subnet in the subnet wizard:

- Private networking, to proactively disable implied public IP addresses for SNAT.

- Created an NSG for CommonSubnet called p-demo01-net-vnet-CommonSubnet-nsg to secure traffic inside the subnet. I will add a DenyAll rule to override the dodgy default 65000 rule.

As you can see, the Virtual Network has not been configured by AVNM yet:

We will have to wait for Azure Policy to execute – or we can force a scan to run against the resource group of the new spoke Virtual Network:

- Az CLI: az policy state trigger-scan –resource-group <resource group name>

- PowerShell: Start-AzPolicyComplianceScan -ResourceGroupName <resource group name>

You could add a command like above into your deployment code if you wished to trigger automatic configuration.

This force process is not exactly quick either! 6 minutes after I forced a policy evaluation, I saw that AVNM was informed about a new Virtual Network:

I returned to AVNM and checked out the Network Groups. The dub01spokes group has a new member:

You can see that a Connectivity Configuration was deployed. Note that the summary doesn’t have any information on Routing Configurations – that’s an oversight by the AVNM team, I guess.

The Virtual Network does have a peering connection to the hub:

The routing has been deployed to the subnet:

A UDR has been created in the Route Table:

Over time, more Virtual Networks are added and I can see from the hub that they are automatically configured by AVNM:

Summary

I have done presentations on AVNM and demonstrated the above configurations in 40 minutes at community events. You could deploy the configurations in under 15 minutes. You can also create them using code! With this setup we can take control of our entire Azure networking deployment – and I didn’t even show you the Admin Rules feature for essential “NSG” rules (they aren’t NSG rules but use the same underlying engine to execute before NSG rules).

Want To Learn More?

Check out my company, Cloud Mechanix, where I share this kind of knowledge through:

- Consulting services for customers and Microsoft partners using a build-with approach.

- Custom-written and ad-hoc Azure training.

Together, I can educate your team and bring great Azure solutions to your organisation.