This post will explain how routing works in Microsoft Azure, and how to troubleshoot your routing issues with Route Tables, BGP, and User-Defined Routes in your virtual network (VNet) subnets and virtual (firewall) appliances/Azure Firewall.

Software-Defined Networking

Right now, you need to forget VLANs, and how routers, bridges, routing switches, and all that crap works in the physical network. Some theory is good, but the practice … that dies here.

Azure networking is software-defined (VXLAN). When a VM sends a packet out to the network, the Azure Fabric takes over as soon as the packet hits the virtual NIC. That same concept extends to any virtual network-capable Azure service. From your point of view, a memory copy happens from source NIC to destination NIC. Yes; under the covers there is an Azure backbone with a “more physical” implementation but that is irrelevant because you have no influence over it.

So always keep this in mind: network transport in Azure is basically a memory copy. We can, however, influence the routing of that memory copy by adding hops to it.

Understand the Basics

When you create a VNet, it will have 1 or more subnets. By default, each subnet will have system routes. The first ones are simple, and I’ll make it even more simple:

- Route directly via the default gateway to the destination if it’s in the same supernet, e.g. 10.0.0.0/8

- Route directly to Internet if it’s in 0.0.0.0/0

By the way, the only way to see system routes is to open a NIC in the subnet, and click Effective Routes under Support & Troubleshooting. I have asked that this is revealed in a subnet – not all VNet-connected services have NICs!

And also, by the way, you cannot ping the subnet default gateway because it is not an appliance; it is a software-defined function that is there to keep the guest OS sane … and probably for us too 😊

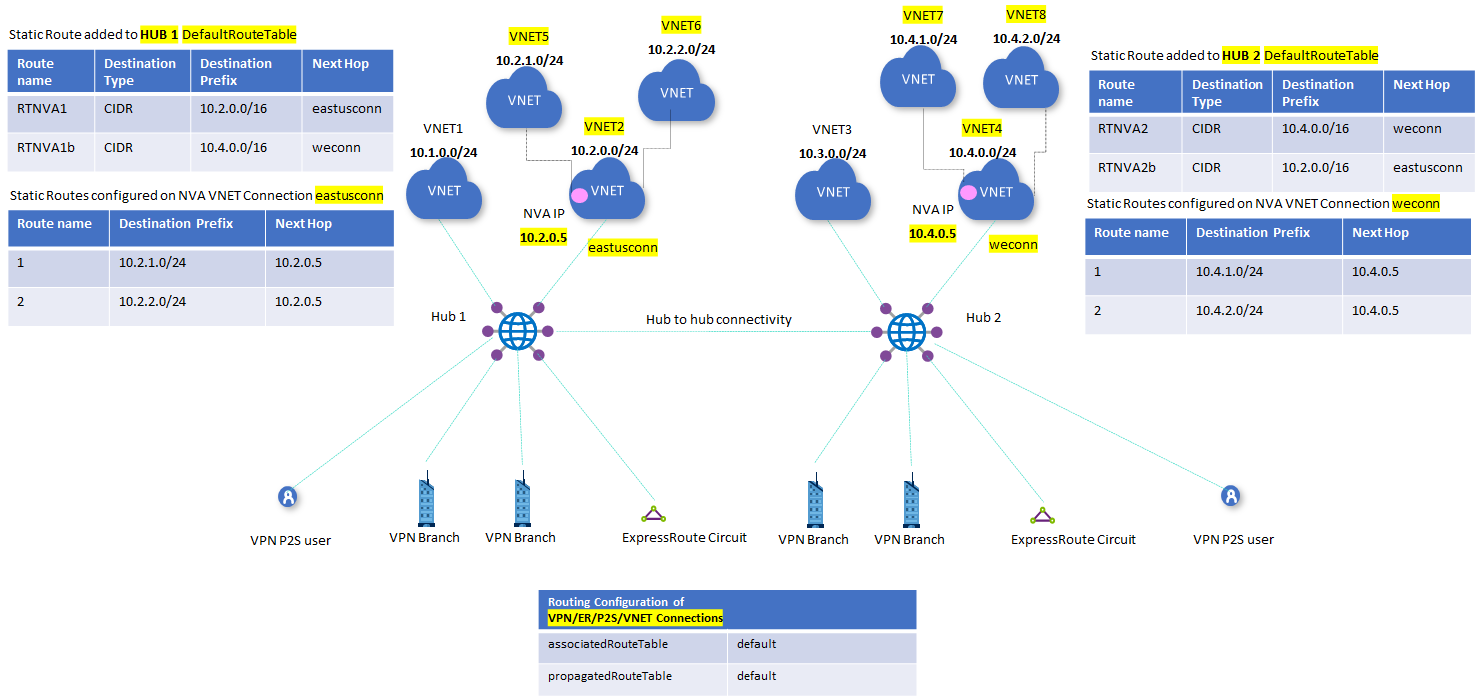

When you peer a VNet with another VNet, you do a few things, including:

- Instructing VXLAN to extend the plumbing of between the peered VNets

- Extending the “VirtualNetwork” NSG rule security tag to include the peered neighbour

- Create a new system route for peering.

The result is that VMs in VNet1 will send packets directly to VMs in VNet2 as if they were in the same VNet.

When you create a VNet gateway (let’s leave BGP for later) and create a load network connection, you create another (set of) system routes for the virtual network gateway. The local address space(s) will be added as destinations that are tunnelled via the gateway. The result is that packets to/from the on-prem network will route directly through the gateway … even across a peered connection if you have set up the hub/spoke peering connections correctly.

Let’s add BGP to the mix. If I enable ExpressRoute or a BGP-VPN, then my on-prem network will advertise routes to my gateway. These routes will be added to my existing subnets in the gateway’s VNet. The result is that the VNet is told to route to those advertised destinations via the gateway (VPN or ExpressRoute).

If I have peered the gateway’s VNet with other VNets, the default behaviour is that the BGP routes will propagate out. That means that the peered VNets learn about the on-premises destinations that have been advertised to the gateway, and thus know to route to those destinations via the gateway.

And let’s stop there for a moment.

Route Priority

We now have 2 kinds of route in play – there will be a third. Let’s say there is a system route for 172.16.0.0/16 that routes to virtual network. In other words, just “find the destination in this VNet”. Now, let’s say BGP advertises a route from on-premises through the gateway that is also for 172.16.0.0/16.

We have two routes for the 172.16.0.0/16 destination:

Azure looks at routes that clash like above and deactivates one of them. Azure always ranks BGP above System. So, in our case, the System route for 172.16.0.0/16 will be deactivated and no longer used. The BGP route for 172.16.0.0/16 via the VNet gateway will remain active and will be used.

Specificity

Try saying that word 5 times in a row after 5 drinks!

The most specific route will be chosen. In other words, the route with the best match for your destination is selected by the Azure fabric. Let’s say that I have two active routes:

- 16.0.0/16 via X

- 16.1.0/24 via Y

Now, let’s say that I want to send a packet to 172.16.1.4. Which route will be chosen? Route A is a 16 bit match (172.16.*.*). Route B is a 24 bit match (172.16.1.*). Route B is a closer match so it is chosen.

Now add a scenario where you want to send a packet to 172.16.2.4. At this point, the only match is Route A. Route B is not a match at all.

This helps explain an interesting thing that can happen in Azure routing. If you create a generic rule for the 0.0.0.0/0 destination it will only impact routing to destinations outside of the virtual network – assuming you are using the private address spaces in your VNet. The subnets have system routes for the 3 private address spaces which will be more specific than 0.0.0.0:

- 168.0.0/16

- 16.0.0/12

- 0.0.0/8

- 0.0.0/0

If your VNet address space is 10.1.0.0/16 and you are trying to send a packet from subnet 1 (10.1.1.0/24) to subnet 2 (10.1.2.0/24), then the generic Route D will always be less specific than the system route, Route C.

Route Tables

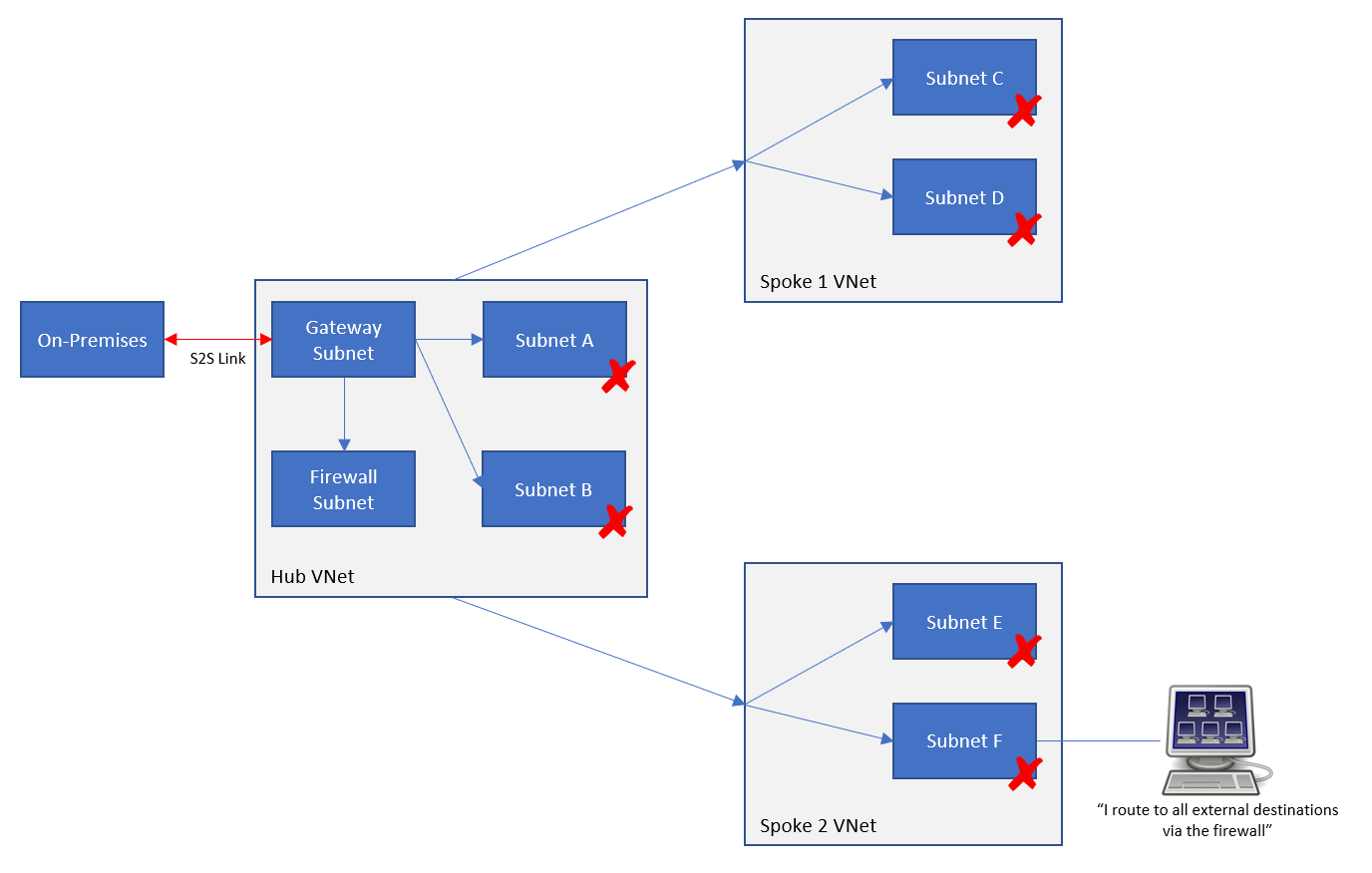

A route table resource allows us to manage the routing of a subnet. Good practice is that if you need to manage routing then:

- Create a route table for the subnet

- Name the route table after the VNet/subnet

- Only use a route table with 1 subnet

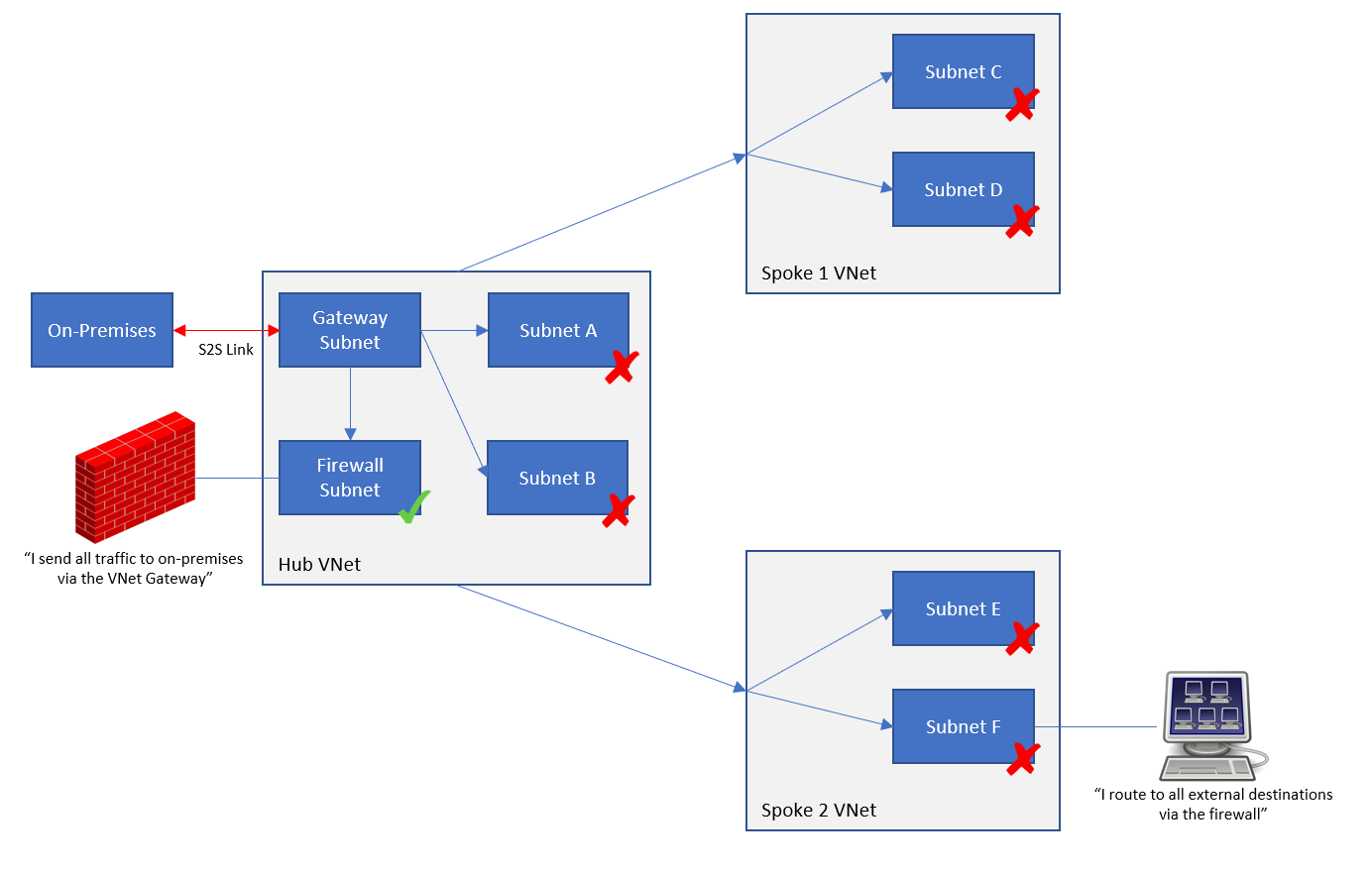

The first thing to know about route tables is that you can control BGP propagation with them. This is especially useful when:

- You have peered virtual networks using a hub gateway

- You want to control how packets get to that gateway and the destination.

The default is that BGP propagation is allowed over a peering connection to the spoke. In the route table (Settings > Configuration) you can disable this propagation so the BGP routes are never copied from the hub network (with the VNet gateway) to the peered spoke VNet’s subnets.

The second thing about route tables is that they allow us to create user-defined routes (UDRs).

User-Defined Routes

You can control the flow of packets using user-defined routes. Note that UDRs outrank BGP routes and System Routes:

- UDR

- BGP routes

- System routes

If I have a system or BGO route to get to 192.168.1.0/24 via some unwanted path, I can add a UDR to 192.168.1.0/24 via the desired path. If the two routes are identical destination matches, then my UDR will be active and the BGP/system route will be deactivated.

Troubleshooting Tools

The traditional tool you might have used is TRACERT. I’m sorry, it has some use, but it’s really not much more than PING. In the software defined world, the default gateway isn’t a device with a hop, the peering connection doesn’t have a hop, and TRACERT is not as useful as it would have been on-premises.

The first thing you need is the above knowledge. That really helps with everything else.

Next, make sure your NSGs aren’t the problem, not your routing!

Next is the NIC, if you are dealing with virtual machines. Go to Effective Routes and look at what is listed, what is active and what is not.

Network Watcher has a couple of tools you should also look at:

- Next Hop: This is a pretty simple tool that tells you the next “appliance” that will process packets on the journey to your destination, based on the actual routing discovered.

- Connection Troubleshoot: You can send a packet from a source (VM NIC or Application Gateway) to a certain destination. The results will map the path taken and the result.

The tools won’t tell you why a routing plan failed, but with the above information, you can troubleshoot a (desired) network path.