In this post, I will explain the types of resources used in Azure Virtual WAN and the nature of their relationships.

Note, I have not included any content on the recently announced preview of third-party NVAs. I have not seen any materials on this yet to base such a post on and, being honest, I don’t have any use-cases for third-party NVAs.

As you can see – there are quite a few resources involved … and some that you won’t see listed at all because of the “appliance-like” nature of the deployment. I have not included any detail on spokes or “branch offices”, which would require further resources. The below diagram is enough to get a hub operational and connected to on-premises locations and spoke virtual networks.

The Virtual WAN – Microsoft.Network/virtualWans

You need at least one Virtual WAN to be deployed. This is what the hub will connect to, and you can connect many hubs to a common Virtual WAN to get automated any-to-any connectivity across the Microsoft physical WAN.

Surprisingly, the resource is deployed to an Azure region and not as a global resource, such as other global resources such as Traffic Manager or Azure DNS.

The Virtual Hub – Microsoft.Network/virtualHubs

Also known as the hub, the Virtual Hub is deployed once, and once only, per Azure region where you need a hub. This hub replaces the old hub virtual network (plus gateway(s), plus firewall, plus route tables) deployment you might be used to. The hub is deployed as a hidden resource, managed through the Virtual WAN in the Azure Portal or via scripting/ARM.

The hub is associated with the Virtual WAN through a virtualWAN property that references the resource ID of the virtualWans resource.

In a previous post, I referred to a chicken & egg scenario with the virtualHubs resource. The hub has properties that point to the resource IDs of each deployed gateway:

- vpnGateway: For site-to-site VPN.

- expressRouteGateway: For ExpressRoute circuit connectivity.

- p2sVpnGateway: For end-user/device tunnels.

If you choose to deploy a “Secured Virtual Hub” there will also be a property called azureFirewall that will point to the resource ID of an Azure Firewall with the AZFW_Hub SKU.

Note, the restriction of 1 hub per Azure region does introduce a bottleneck. Under the covers of the platform, there is actually a virtual network. The only clue to this network will be in the peering properties of your spoke virtual networks. A single virtual network can have, today, a maximum of 500 spokes. So that means you will have a maximum of 500 spokes per Azure region.

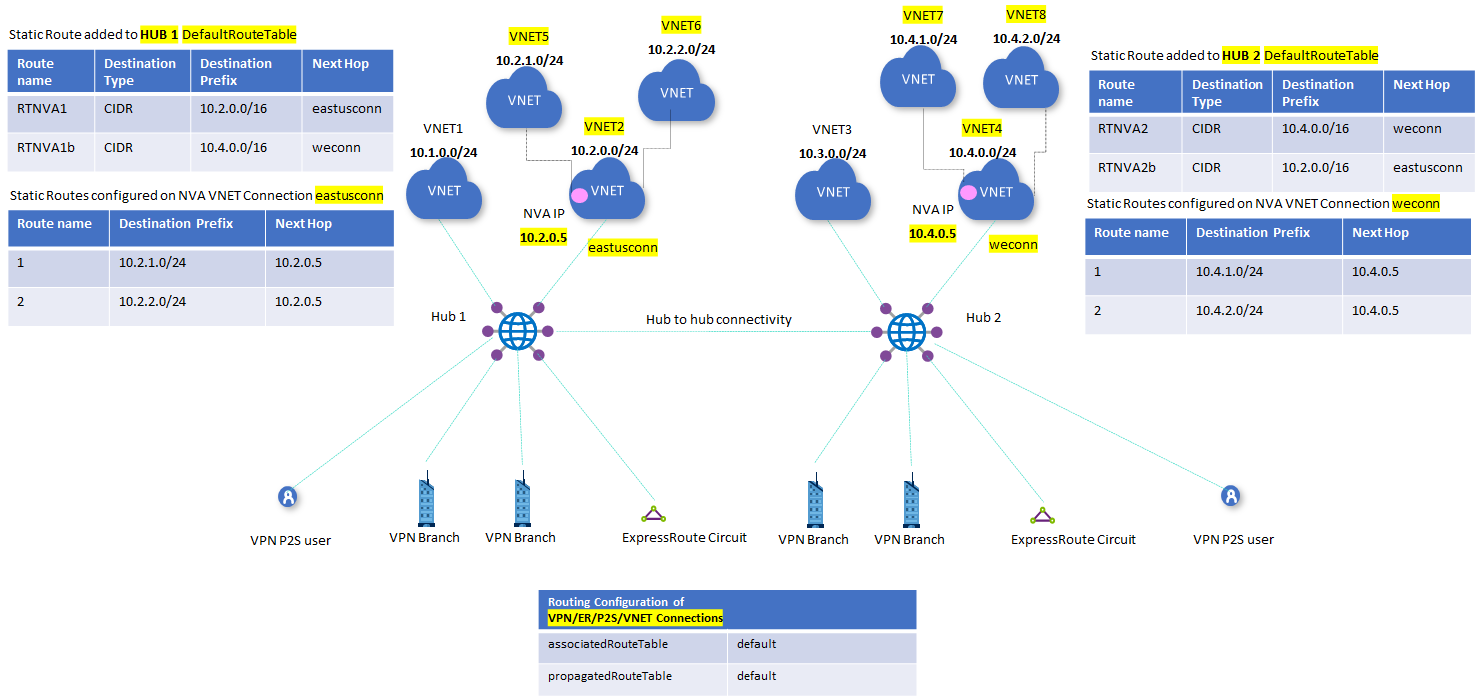

Routing Tables – Microsoft.Network/virtualHubs/hubRouteTables & Microsoft.Network/virtualHubs/routeTables

These are resources that are used in custom routing, a recently announced as GA feature that won’t be live until August 3rd, according to the Azure Portal. The resource control the flows of traffic in your hub and spoke architecture. They are child-resources of the virtualHubs resource so no references of hub resource IDs are required.

Azure Firewall – Microsoft.Network/azureFirewalls

This is an optional resource that is deployed when you want a “Secured Virtual Hub”. Today, this is the only way to put a firewall into the hub, although a new preview program should make it possible for third-parties to join the hub. Alternatively, you can use custom routing to force north-south and east-west traffic through an NVA that is running in a spoke, although that will double peering costs.

The Azure Firewall is deployed with the AZFW_Hub SKU. The firewall is not a hidden resource. To manage the firewall, you must use an Azure Firewall Policy (aka Azure Firewall Manager). The firewall has a property called firewallPolicy that points to the resource ID of a firewallPolicies resource.

Azure Firewall Policy – Microsoft.Network/firewallPolicies

This is a resource that allows you to manage an Azure Firewall, in this case, an AZFW_Hub SKU of Azure Firewall. Although not shown here, you can deploy a parent/child configuration of policies to manage firewall configurations and rules in a global/local way.

VPN Gateway – Microsoft.Network/vpnGateways

This is one of 3 ways (one, two or all three at once) that you can connect on-premises (branch) sites to the hub and your Azure deployment(s). This gateway provides you with site-to-site connectivity using VPN. The VPN Gateway uses a property called virtualHub to point at the resource ID of the associated hub or virtualHubs resource. This is a hidden resource.

Note that the virtualHubs resource must also point at the resource ID of the VPN gateway resource ID using a property called vpnGateway.

ExpressRoute Gateway – Microsoft.Network/expressRouteGateways

This is one of 3 ways (one, two or all three at once) that you can connect on-premises (branch) sites to the hub and your Azure deployment(s). This gateway provides you with site-to-site connectivity using ExpressRoute. The ExpressRoute Gateway uses a property called virtualHub to point at the resource ID of the associated hub or virtualHubs resource. This is a hidden resource.

Note that the virtualHubs resource must also point at the resource ID of the ExpressRoute gateway resource ID using a property called p2sGateway.

Point-to-Site Gateway – Microsoft.Network/p2sVpnGateways

This is one of 3 ways (one, two or all three at once) that you can connect on-premises (branch) sites to the hub and your Azure deployment(s). This gateway provides users/devices with connectivity using VPN tunnels. The Point-to-Site Gateway uses a property called virtualHub to point at the resource ID of the associated hub or virtualHubs resource. This is a hidden resource.

The Point-to-Site Gateway inherits a VPN configuration from a VPN configuration resource based on Microsoft.Network/vpnServerConfigurations, referring to the configuration resource by its resource ID using a property called vpnServerConfiguration.

Note that the virtualHubs resource must also point at the resource ID of the Point-to-Site gateway resource ID using a property called p2sVpnGateway.

VPN Server Configuration – Microsoft.Network/vpnServerConfigurations

This configuration for Point-to-Site VPN gateways can be seen in the Azure WAN and is intended as a shared configuration that is reusable with more than one Point-to-Site VPN Gateway. To be honest, I can see myself using it as a per-region configuration because of some values like DNS servers and RADIUS servers that will probably be placed per-region for performance and resilience reasons. This is a hidden resource.

The following resources were added on 22nd July 2020:

VPN Sites – Microsoft.Network/vpnSites

This resource has a similar purpose to a Local Network Gateway for site-to-site VPN connections; it describes the on-premises location, AKA “branch office”. A VPN site can be associated with one or many hubs, so it is actually connected to the Virtual WAN resource ID using a property called virtualWan. This is a hidden resource.

An array property called vpnSiteLinks describes possible connections to on-premises firewall devices.

VPN Connections – Microsoft.Network/vpnGateways/vpnConnections

A VPN Connections resource associates a VPN Gateway with the on-premises location that is described by an associated VPN Site. The vpnConnections resource is a child resource of vpnGateways, so there is no actual resource; the vpnConnections resource takes its name from the parent VPN Gateway, and the resource ID is an extension of the parent VPN Gateway resource ID.

By necessity, there is some complexity with this resource type. The remoteVpnSite property links the vpnConnections resource with the resource ID of a VPN Site resource. An array property, called vpnSiteLinkConnections, is used to connect the gateway to the on-premises location using 1 or 2 connections, each linking from vpnSiteLinkConnections to the resource/property ID of 1 or 2 vpnSiteLinks properties in the VPN Site. With one site link connection, you have a single VPN tunnel to the on-premises location. With 2 link connections, the VPN Gateway will take advantage of its active/active configuration to set up resilient tunnels to the on-premises location.

Virtual Network Connections – Microsoft.Network/virtualHubs/hubVirtualNetworkConnections

The purpose of a hub is to share resources with spoke virtual networks. In the case of the Virtual Hub, those resources are gateways, and maybe a firewall in the case of Secured Virtual Hub. As with a normal VNet-based hub & spoke, VNet peering is used. However, the way that VNet peering is used changes with the Virtual Hub; the deployment is done using the hub/VirtualNetworkConnections child resource, whose parent is the Virtual Hub. Therefore, the name and resource ID are based on the name and resource ID of the Virtual Hub resource.

The deployment is rather simple; you create a Virtual Network Connection in the hub specifying the resource ID of the spoke virtual network, using a property called remoteVirtualNetwork. The underlying resource provider will initiate both sides of the peering connection on your behalf – there is no deployment required in the spoke virtual network resource. The Virtual Network Connection will reference the Hub Route Tables in the hub to configure route association and propagation.

More Resources

There are more resources that I’ve yet to document, including: