In this post, I will discuss the recent news that Azure is having some serious capacity issues affecting customers in 2022 that could last into 2023.

The News

Personally, I didn’t think that Azure having capacity issues was news. I thought that thanks to all the jokes on social media, everyone took it for granted that the effects of the pandemic and cargo crises had crippled electronics supplies the world over. Even the recent news that the annual MVP renewal (July 1st) was being postponed to July 5 was jokingly blamed on the capacity issues.

Last Friday, The Information (subscription required) reported:

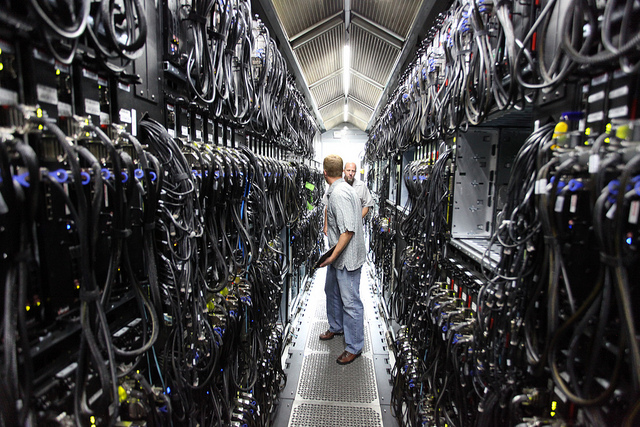

… more than two dozen Azure data centers in countries around the world are operating with limited server capacity available to customers, according to two current Microsoft managers contending with the issue and an engineer who works for a major customer.

This is not the news we want to hear when there are repeated reports that cloud adoption is increasing, Azure adoption is growing faster than AWS adoption, and Microsoft’s total (including SaaS) cloud business is (marginally) the largest in the industry.

The Effect

Most people who have used Azure for a few years have seen the dreaded deployment fails – you cannot get capacity because the region you have selected doesn’t have it. And the “helpful” support agent tells you to try a less-impacted region on another continent.

That suggestion indicates how little that person cares or the lack of understanding about IT performance or compliance issues.

I work mostly with Norwegian clients. Typically, they need to stay inside the EU (using West Europe, the largest hero region), and often they have to stay inside Norway (Norway East, because Norway West is not publicly available to customers). If one of those clients tries to start something or create something in their chosen region then being told to deploy in Asia or the US isn’t going to work. If they chose Norway East because they need to comply with the local “Arkiv” (archive) law then venturing outside the border is not an option.

Let’s say you’ve built a highly integrated system in West US. You have lots of containers and functions, all integrating with each other, and hitting databases. Your workload is time-sensitive so you need to minimise every millisecond of latency. Heck, you have even started to use VMs to get access to proximity placement groups to control physical distances between tiers of your workloads. And then a support engineer tells you that your additional scale-out capacity should be halfway around the planet? Seriously?

Solutions

Other than some miracle where manufacturing backlogs and shipping mismanagement are solved, you will need to minimise risks of this sort of thing happening to you.

Auto-Scaling

Customers use auto-scaling to reduce costs. You dynamically create or power-up (allocate to a running/billing state) compute instances to stay slightly ahead of demand. And when demand (profits) reduce, you dynamically destroy or power down (deallocate to a stopped/non-billing state) unneeded compute instances.

When capacity is not available, auto-scaling can be a gamble. You want to minimise wastage during non-peak periods, but not having enough compute instances could damage revenue/operations more than having unused compute instances. For example, your Citrix/Azure Virtual Desktop instances are required for people to work, but when people try to log in on Monday morning, Azure cannot supply enough machines to scale-out your worker pools. Whoops! You saved some money over the weekend, but now only a small percentage of your employees can work.

In these times of shortage, you need to hold on to what you have got. It is worth considering the disablement of auto-scaling and going back to old practices of trying to figure out what you need, and keeping that capacity running.

Virtual Machine Migration

After the summer, I will have some involvement in three migration projects. Two of those could result in large numbers of virtual machines being deployed to Azure. All three projects have hard deadlines for completion. The last thing that those clients are going to want to hear is: “Sorry, your business plans are not feasible because there aren’t enough servers in the Cloud that IT has selected”.

Microsoft offers a program where you can reserve virtual machine capacity for selected series of virtual machines, called On-demand Capacity Reservation. In short, you pay for the price of the machine you want, before you deploy it, to guarantee the capacity that you want when you need it later.

Or as some cynics might say: you pay a vig to Microsoft for capacity that you should have expected in a hyper-scale cloud in the first place.

If you are in a scenario where you have an upcoming spike in capacity, such as a migration, and you need to be sure the capacity will be there, then this form of reservation must be strongly considered. However, telling a client that they need to pay for compute weeks before they need it – will be a hard sell.

SKU Choice

When we deploy new tech, we always want the latest and greatest. Why would you deploy a years-old D_v3 when there’s a D_v5 with a faster processor? If you really need the performance of the newer SKU, then I get the choice. But how many workloads genuinely need that kind of sizing. I’ve rarely encountered one.

Under the covers of the platform, that v5 is limited to new hardware with matching physical processors. That is the same capacity that Microsoft (and others) cannot get their hands on. However, the v3 is able to run on the v3 hardware, and thanks to Hyper-V processor management features, it is also able to run on newer hardware. So if you want more potential host capacity to run your compute instances, then you will choose older SKUs that run on older processors.

This advice will apply to any resource type – not just virtual machines. In the end, everything (including so-called serverless computing) is a virtual machine under the platform, except for items such as VMware hosts and SAP Hana machines which are physical servers.

Summary

It sounds like we are facing some issues. Azure might be making the headlines now, but Microsoft uses the same physical components as everyone else – there is only AMD and Intel, pretty much everything electronic is assembled in China, and everything needs months to move by cargo ship. We are going to have to box clever to ensure that we have enough capacity for resources such as virtual machines, app services, containers, databases, and so on – everything that relies on compute instances under the covers.

One thought on “Dealing With Azure Capacity Shortages”