How do you run multiple virtual machines on different subnets? Forget for for just a moment that these are virtual machines. How would you do it if they were physical machines? The network administrators would set up a Virtual Local Area Network or VLAN. A VLAN is a broadcast domain, i.e. it is a single subnet and broadcasts cannot be transmitted beyond its boundaries without some sort of forwarder to convert the broadcast into a unicast. Network administrators use VLAN’s for a bunch of reasons:

- Control broadcasts because they can become noisy.

- They need to be creative with IP address ranges.

- The want to separate network devices using firewalls.

That last one is why we have multiple VLAN’s at work. Each VLAN is firewalled from every other VLAN. We open up what ports we need to between VLAN’s and to/from the Internet.

Each VLAN has an ID. That is used by administrators for configuring firewall rules, switches and servers.

How do you tell a physical server that it is on a VLAN?

There’s two ways I can think of:

- The network administrators would assign the switch ports that will connect the server to a specific VLAN

- The network administrators can create a “trunk” on a switch port. That’s when all VLAN’s are available on that port. Then on the server you need to use the network card driver or management software to specify which VLAN to bind the NIC to. Some software (HP NCU) allows you to create multiple virtual network cards to bind the server to multiple VLAN’s using one physical NIC.

How about a virtual machine; how do you bind the virtual NIC of a virtual machine to a specific VLAN? It’s a similar process. I must warn anyone reading this that I’ve worked with a Cisco CCIE while working on Hyper-V and previously with another senior Cisco guy while working on VMware ESX and neither of them could really get their heads around this stuff. Is it too complicated for them? Hardly. I think the problem was that it was too simple! Seriously!

Let’s have a look at the simplest virtual networking scenario:

The host server has a single physical NIC to connect virtual machines. A virtual switch is created in Hyper-V to pass the physical network that is attached to that NIC to any VM that is bound to that virtual switch.

The host server has a single physical NIC to connect virtual machines. A virtual switch is created in Hyper-V to pass the physical network that is attached to that NIC to any VM that is bound to that virtual switch.

You can see above that the switch only operates with VLAN 101. Every server on the network operates on VLAN 101. The physical servers are on it, the parent partition of the host is on it, etc. The physical switch port is connected to the virtual machine NIC in the host using a physical network cable. In Hyper-V, the host administrator creates a virtual switch.

Network admins: Here’s where you pull what hair you have left out. This is not a switch like you think of a switch. There is no console, no MIB, no SNMP, no ports, no spanning tree loops, nada! It is a software connection and network pass through mechanism that exists only in the memory of the host. It interacts in no way with the physical network. You don’t need to architect around them.

The virtual switch is a linking mechanism. It connects the physical network card to the virtual network card in the virtual machine. It’s as simple as that. In this case both of the VM’s are connected to the single virtual switch (configured as an External type). That means they too are connected to VLAN 101.

How do we get multiple Hyper-V virtual machines to connect to multiple VLAN’s? There’s a few ways we can attack this problem.

Multiple Physical NIC’s

In this scenario the physical host server is configured with multiple NIC’s.

*Rant Alert* Right, there’s a certain small number of journalists/consultants who are saying “you should always try to have 1 NIC for every VM on the host”. Duh! Let’s get real. Most machines don’t use their GB connections in a well designed and configured network. That nightly tape backup over the network design is a dinosaur. Look at differential, block level continuous incremental backups instead, e.g. Microsoft System Center Data Protection Manager or Iron Mountain Live Vault. Next, who has money to throw at installing multiple quad NIC’s with physical switch ports all over the place. The idea here is to consolidate! Finally, if you are dealing with blade servers you only have so many mezzanine card slots and enclosure/chassis device slots. If a blade can have 144GB of RAM, giving maybe 40+ VM’s, that’s an awful lot of NIC’s you’re going to need :) Sure there are scenarios where a VM might need a dedicated NIC but there are extremely rare. *Rant Over*

In this situation the network administrator has set up two ports on the switches, one for each VLAN to connect to the Hyper-V host. VLAN 101 has a physical port on the switch that is cabled to NIC 1 on the host. VLAN 102 has a physical port on the switch that is cabled to NIC 2 on the host. The parent partition has it’s own NIC, not shown. Virtual Switch 1 is created and connected to NIC 1 and Virtual Switch 2 is created and connected to NIC 2. Every VM that needs to talk on VLAN 101 will be connected to Virtual Switch 1 by the host administrator. Every VM that needs to talk on VLAN 102 should be connected to Virtual Switch 2 by the host administrator.

In this situation the network administrator has set up two ports on the switches, one for each VLAN to connect to the Hyper-V host. VLAN 101 has a physical port on the switch that is cabled to NIC 1 on the host. VLAN 102 has a physical port on the switch that is cabled to NIC 2 on the host. The parent partition has it’s own NIC, not shown. Virtual Switch 1 is created and connected to NIC 1 and Virtual Switch 2 is created and connected to NIC 2. Every VM that needs to talk on VLAN 101 will be connected to Virtual Switch 1 by the host administrator. Every VM that needs to talk on VLAN 102 should be connected to Virtual Switch 2 by the host administrator.

Virtual Switch Binding

You can only bind one External type virtual switch to a NIC. So in the above example we could not have matched up two virtual switches to the first NIC and changed the physical switch port to be a network trunk. We can do something similar but different.

When we create an external virtual switch we can tell it to only communicate on a specific VLAN. You can see in the above screenshot that I’ve built a new virtual switch and instructed it to use the VLAN ID (or tag) of 102. That means that every VM virtual NIC that connects to this virtual switch will expect to be on VLAN 102 with no exceptions.

When we create an external virtual switch we can tell it to only communicate on a specific VLAN. You can see in the above screenshot that I’ve built a new virtual switch and instructed it to use the VLAN ID (or tag) of 102. That means that every VM virtual NIC that connects to this virtual switch will expect to be on VLAN 102 with no exceptions.

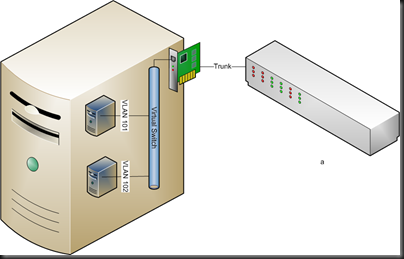

Taking our previous example, here’s how this would look:

The network administrator has done things slightly different this time. Instead of configuring the two physical switch ports to be bound to specific VLAN’s they’re simple configured trunks. That means many VLAN’s are available on that port. The device communicating on the trunk must specify what VLAN it is on to communicate successfully. Worried about security? As long as you trust the host administrator to get things right you are OK. Users of the virtual machines cannot change their VLAN affiliation.

The network administrator has done things slightly different this time. Instead of configuring the two physical switch ports to be bound to specific VLAN’s they’re simple configured trunks. That means many VLAN’s are available on that port. The device communicating on the trunk must specify what VLAN it is on to communicate successfully. Worried about security? As long as you trust the host administrator to get things right you are OK. Users of the virtual machines cannot change their VLAN affiliation.

You can see that virtual switch 1 is now bound to VLAN 101. Every VM that connects to virtual switch 1 will be only able to communicate on VLAN 101 via the trunk on NIC 1. It’s similar on NIC 2. It’s set up with a virtual switch on VLAN 102 and all bound VM’s can only communicate on that VLAN.

We’ve changed where the VLAN responsibility lies but we haven’t solved the hardware costs and consolidation issue.

VLAN ID on the VM

Here’s the solution you are most likely to employ. For the sake of simplicity let’s forget about NIC teaming for a moment.

Instead of setting the VLAN on the virtual switch we can do it in the properties of the VM. To be more precise we can do it in the properties of the virtual network adapter of the VM. You can see that I’ve done this above by configuring the network adapter to only communicate on VLAN (ID or tag) 102.

Instead of setting the VLAN on the virtual switch we can do it in the properties of the VM. To be more precise we can do it in the properties of the virtual network adapter of the VM. You can see that I’ve done this above by configuring the network adapter to only communicate on VLAN (ID or tag) 102.

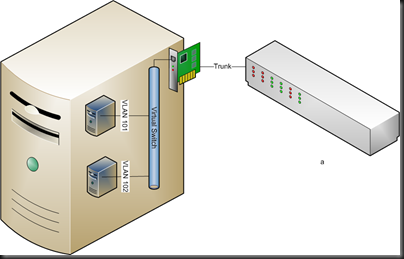

This is how it looks in our example:

Again, the network administrator has set up a trunk on the physical switch port. A single external virtual switch is configured and no VLAN ID is specified. The two VM’s are set up and connected to the virtual switch. It is here that the VLAN specification is done. VM 1 has it’s network adapter configured to talk on VLAN 101. VM 2 is configured to operate on VLAN 102. And it works, just like that!

Again, the network administrator has set up a trunk on the physical switch port. A single external virtual switch is configured and no VLAN ID is specified. The two VM’s are set up and connected to the virtual switch. It is here that the VLAN specification is done. VM 1 has it’s network adapter configured to talk on VLAN 101. VM 2 is configured to operate on VLAN 102. And it works, just like that!

Waiver: I’m seeing a problem where VMM created NIC’s do not bind to a VLAN. Instead I have to create the virtual network adapter in the Hyper-V console.

Here’s one to watch out for if you use the self servicing console. If you cannot trust delegated administrators/users to get VLAN ID configuration right or don’t trust them security-wise then do not allow them to alter VM configurations. If you do then they can alter the VLAN ID and put their VM into a VLAN that it might not belong to.

Firewall Rules

Unless network administrators allow it, virtual machines on VLAN 101 cannot see virtual machines on VLAN 102. A break out is theoretically impossible due to the architecture of Hyper-V leveraging the No eXecute Bit (AKA DEP or Data Execution Prevention).

Summary

You can see that you can set up a Hyper-V host to run VM’s on different VLAN’s. You’ve got different ways to do it. You can even see that you can use your VLAN’s to firewall VM’s from each other. Hopefully I’ve explained this in a way that you can understand.