I see many bad designs where people bring cable-oriented designs from physical locations into Azure. I hear lots of incorrect assumptions when people are discussing network designs. For example: “I put shared services in the hub because they will be closer to their clients”. Or my all-time favourite: people assuming that ingress traffic from site-to-site connections will go through a hub firewall because it’s in the middle of their diagram. All this is because of one common mistake – people don’t realise that Azure Virtual Networks do not exist.

Some Background

Azure was designed to be a multi-tenant cloud capable of hosting an “unlimited” number of customers.

I realise that “unlimited” easily leads us to jokes about endless capacity issues 🙂

Traditional hosting (and I’ve worked there) is based on good old fashioned networking. There’s a data centre. At the heart of the data centre network there is a network core. The entire facility has a prefix/prefixes of address space. Every time that a customer is added, the network administrators carve out a prefix for the new customer. It’s hardly self-service and definitely not elastic.

Azure settled on VXLAN to enable software-defined networking – a process where customer networking could be layered upon the physical networks of Microsoft’s physical data centres/global network.

Falling Into The Myth

Virtual Networks make life easy. Do you want a network? There’s no need to open a ticket? You don’t need to hear from a snarky CCIE who snarls when you ask for a /16 address prefix as if you’ve just asked for Flash “RAID10” from a SAN admin. No; you just open up the Portal/PowerShell/VS Code and you deploy a network of whatever size you want. A few seconds later, it’s there and you can start connecting resources to the new network.

You fire up a VM and you get an address from “DHCP”. It’s not really DHCP. How can it be when Azure virtual networks do not support broadcasts or multicasts? You log into that VM and have networking issues so you troubleshoot like you learn how to:

- Ping the local host

- Ping the default gateway – oh! That doesn’t work.

- Traceroute to a remote address – oh! That doesn’t work either.

And then you start to implement stuff just like you would in your own data centre.

How “It Works”

Let me start by stating that I do not know how the Azure fabric works under the covers. Microsoft aren’t keen on telling us how the sausage is made. But I know enough to explain the observable results.

When you click the Create button at the end of the Create Virtual Machine wizard, an operator is given a ticket, they get clearance from data center security, they grab some patch leads, hop on a bike, and they cycle as fast as they can to the patch panel that you have been assigned in Azure.

Wait … no … that was a bad stress dream. But really, from what I see/hear from many people, they think that something like that happens. Even if that was “virtual”, the who thing just would not be scaleable.

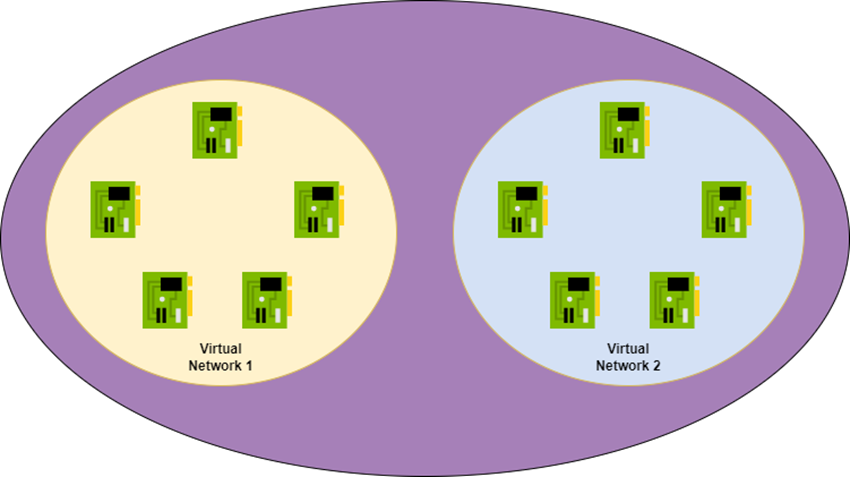

Instead, I want you to think of an Azure virtual network as a Venn diagram. The process of creating a virtual network instructs the Azure fabric that any NIC that connects to the virtual network can route to any other NIC in the virtual network.

Two things here:

- You should take “route” as meaning a packet can go from the source NIC to the destination NIC. It doesn’t mean that it will make it through either NIC – we’ll cover that topic in another post soon.

- Almost everything in Azure is a virtual machine at some level in Azure. For example, “serverless” Functions run in Microsoft-managed VMs in a Microsoft tenant. Microsoft surfaces the Function functionality to you in your tenant. If you connect those PaaS services (like ASE or SQL Manage Instance) to your virtual network then there will be NICs that connect to a subnet.

Connecting a NIC to a virtual network adds the new NIC to the Venn Diagram. The Azure fabric now knows that this new NIC should be able to route to other NICs in the same virtual network and all the previous NICs can route to it.

Adding Virtual Network Peering

Now we create a second virtual network. We peer those virtual networks and then … what happens now? Does a magic/virtual pipe get created? Nope – it’s fault tolerant so two magic/virtual lines connect the virtual networks? Nope. It’s Venn diagram time again.

The Azure fabric learns that the NICs in Virtual Network 1 can now route to the NICs in Virtual Network 2 and vice versa. That’s all. There is no magic connection. From a routing/security perspective, the NICs in Virtual Network 1 are no different to the NICs in Virtual Network 2. You’ve just created a bigger mesh from (at least) two address prefixes.

Repeat after me:

Virtual networks do not exist

How Do Packets Travel?

OK Aidan (or “Joe” if you arrived here from Twitter), how the heck do packets get from one NIC to another?

Let’s melt some VMware fanboy brains – that sends me to my happy place. Aure is built using Windows Server Hyper-V; the same Hyper-V that you get with commercially available Windows Server. Sure, Azure layers a lot of stuff on top of the hypervisor, but if you dig down deep enough, you will find Hyper-V.

Virtual machines, your or those run by Microsoft, are connected to a virtual switch on the host. The virtual switch is connected to a physical ethernet port on the host. The host is addressable on the Microsoft physical network.

You come along and create a virtual network. The fabric knows to track NICs that are being connected. You create a virtual machine and connect it to the virtual network. Azure will place that virtual machine on one host. As far as you are concerned, that virtual machine has an address from your network.

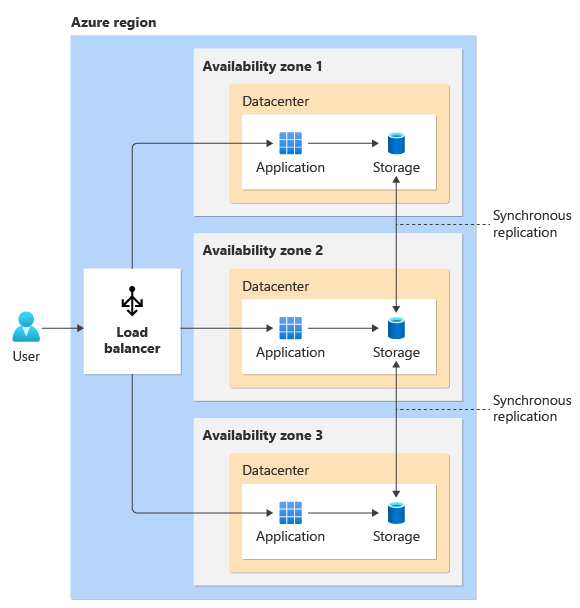

You then create a second VM and connect it to your virtual network. Azure places that machine on a different host – maybe even in a different data centre. The fabric knows that both virtual machines are in the same virtual network so they should be able to reach each other.

You’ve probably use a 10.something address, like most other customers, so how will your packets stay in your virtual network and reach the other virtual machine? We can thank software-defined networking for this.

Let’s use the addresses of my above diagram for this explanation. The source VM has a customer IP address of 10.0.1.4. It is sending a packet to the destination VM with a customer address of 10.0.1.5. The packet will leave the source NIC, 10.0.1.4 and reaches the host’s virtual switch. This is where the magic happens.

The packet is encapsulated, changing the destination address to that of the destination virtual machine’s host. Imagine you are sending a letter (remember those?) to an apartment number. It’s not enough to say “Apartment 1”; you have to include other information to encapsulate it. That’s what the fabric enables by tracking where your NICs are hosted. Encapsulation wraps the customer packet up in an Azure packet that is addressed to the host’s address, capable of travelling over the Microsoft Global Network – supporting single virtual networks and peered (even globally) virtual networks.

The packet routes over the Microsoft physical network unbeknownst to us. It reaches the destination host, and the encapsulation is removed at the virtual switch. The customer packet is dropped into the memory of the destination virtual machine and Bingo! the transmission is complete.

From our perspective, the packet routes directly from source to destination. This is why you can’t ping a default gateway – it’s not there because it plays no role in routing because: the virtual network does not exist.

I want you to repeat this:

Packets go directly from source to destination

Two Most Powerful Pieces Of Knowledge

If you remember …

- Virtual networks do not exist and

- Packets go directly from source to destination

… then you are a huge way along the road of mastering Azure networking. You’ve broken free from string theory (cable-oriented networking) and into quantum physics (software-defined networking). You’ll understand that segmenting networks into subnets for security reasons makes no sense. You will appreciate that placing “shared services” in the hub offered no performance gain (and either broke your security model or made it way more complicated).